The Spring 2024 auction of the Enakor Auction House is dedicated to jewellery, but there is also another small highlight – thirty works of fine art, most of which can no doubt also be defined as “jewels”. Most of them are works by Bulgarian artists, with one exception – Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669).

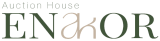

A contemporary print (probably 20th century) of a New Testament-themed engraving by Rembrandt is included in the Easter auction, in honour of the approaching greatest Christian holiday – the Resurrection of Christ. It is one of the great Netherlander’s most famous and highly prized works, The Three Crosses (“Christ Crucified Between Two Thieves“), drypoint and burin, Phase III of V, 1653, which depicts the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

How we perceive the great Rembrandt today

Todor Petev, in the publication “In the Mirror of Rembrandt” (Petev 2024:11-13), studies and catalogue to the exhibition of Rembrandt’s prints at the NBU’s UniArt Gallery, writes the following about the etcher Rembrandt: “Today Rembrandt is one of the most widely known and most studied engravers. Nevertheless, this was far from always the case. In 1669, he died in Amsterdam, far past the height of his fame, bankrupt, penniless, buried in a nameless rented grave. … Critics of the time dismissed him for his lack of classical perception of form and for his drastic “illiterate” realism. However, from the 1830s onwards, a number of French artists rebelled against the conservative rules of the Academy and rediscovered Rembrandt as an artist who aspired to realism and artistic innovation. His figure became a myth – the ultimate outsider, rebel and misunderstood genius. …

In the nineteenth century, the Bohemian, the Liberal and the Romantic joined Rembrandt’s disguises. Consistent, often at odds with one another, critics and artistic currents – Romantics, Realists, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and so on – recognized in him an anti-academic cult figure, a precursor who embodied their ideals and goals. …

Yet why is he so appealing to the public and professionals? His contemporaries and subsequent admirers alike pay attention to the vivid emotions the Dutch engraver conveys without sentimentality; the insightful narratives he presents; the visual equivalents of psychological and spiritual states, the subtle suggestions; of the eloquent language of body and gesture reflected in the medium; of the expressive power of the symbolic dialogue between darkness and light, the principal actors in his scenes; of Rembrandt’s reworking of his plates again and again in constant search of new ideas … It is an endless sea of spirited visual presence.”

Nikolay Raynov sees Rembrandt as follows (Raynov 1938: 48-49, quoted in Petev 2024: 47): “But the painting and graphic sensations which he received from the nature he studied, fused in his strong imagination, and from the fusion unseen forms poured out … He transformed the copper engraving. He did not draw the incisors with deliberate and diligent precision like his contemporaries, but with a fervent passion; he cut the incisions as it suited him, so long as he obtained a deep darkness – the opposite of blinding light … a man endowed with superhuman transformative power. His imagination acts magically … He takes reality in its stark form, but gives it power, raises it to a strange expressiveness, and it becomes like a vision; the image becomes fabulous … The material world and the spiritual world are united by the intervention of light. A single ray appears – and the presence of God is already felt. But this intervention of the spiritual and eternal in the world of mortal beings is simple and natural … In each of the engravings the composition starts from the luminous hearth – a candlestick, a supernatural radiance or a flash of lightning. This light gives a strange otherworldliness to the painted scenes – and they haunt us like striking dreams.”

The story of the engraving “The Three Crosses”, 1653.

Rembrandt’s genius as an engraver is demonstrated in his use of drypoint, which he began adding to his etchings in the 1640s (Princeton). He was the first artist to take full advantage of the dark velvety richness and painting effects of drypoint created by the ink or metallic residue left by fine lines scratched directly into the copper plate with a needle (Orenstein 1995). Despite the fragility of the incisor, which quickly wears away with each impression, Rembrandt used drypoint increasingly and almost exclusively in several masterpieces of the 1650s, including “The Three Crosses”, in which he also applied corrections with burin from the third stage onwards.

One of Rembrandt’s greatest works in any medium (Metropolitan Museum), this profound and evocative interpretation of Christ’s crucifixion undergoes an unusually drastic conceptual and physical reworking in five stages (Princeton). It is considered one of the most dynamic prints ever made. The work is recognized not only as a high point in Rembrandt’s printmaking, but also as a milestone in the history of the graphic arts in general.

“The Three Crosses” depicts St. Luke’s account of the events of Golgotha. The upper third of the print is filled with a dark sky, while the emaciated body of Christ, bathed in a beam of bright celestial light, is shown crucified in the centre. Two crosses flank him with the crucified thieves. Below him are mourning figures, including Mary Magdalene, John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary. The Virgin Mary is represented as losing consciousness from despair and is supported by John the Evangelist.

To the left of Golgotha is a group of Roman soldiers, most of whom are equestrians with spears. A centurion of the Roman army kneels before the cross of Christ with his helmet removed; showing the dramatic moment of his conversion to the faith at the moment Christ breathed his last breath. In the middle foreground, two turbaned figures walk to the right, followed by a dog looking at Christ. In foreground left, group of men conversing. There is a black shadow of some kind, perhaps a pit, in the lower right, and bushes behind it in the third foreground.

The work was created using the drypoint technique, which involves scratching lines directly into a copper plate with a stylus. The carved lines have rough edges, known as “burr,” which absorb the ink and give the printed lines a dark, velvety appearance (Christie’s). Rembrandt boldly incised a combination of hard, straight lines, dense cross-hatching, and light, loose sketches to create highly contrasting passages of light and dark, a sense of movement and drama. In some places, he scrapes the edge to avoid blurring the lines. When Rembrandt created this print, he deliberately left ink on the printing plate (Orenstein 1995). This ink lightly covers the figures standing at the foot of the cross on the right. A thicker layer almost completely covers the bushes along the right edge. The engraver plays with the amount of ink, erasing some patches to leave some figures bathed in celestial light, while others are covered in dark shadows. The effect of these powerful tonal contrasts is known as chiaroscuro (Christie’s).

By creatively adding the ink to the copper plate, Rembrandt in a sense paints each print. Each time he prints the copper plate, he creates a unique work. He further varied the prints by printing them on different media – paper, parchment (Metropolitan). Parchment, for example, which is less absorbent than paper, holds the ink on the surface, softening the lines and increasing the richness of the overall effect.

Rembrandt created four different versions, ‘states’ or ‘phases’, of The Three Crosses, each time reworking the copper plate to change the image. In the first phase, the overall composition was created. Twenty-one original impressions of it are known (Christie’s). For the second phase, Rembrandt added several shading lines at the right edge. There are 10 original prints documented from this phase.

The contemporary print offered in the Enakor Auction House Spring Auction is from the third phase where Rembrandt increased the shading to heighten the drama. In this phase, Rembrandt signed and dated the plate bottom centre “Rembrandt.f.1653,” indicating that this was the version of “The Three Crosses”, he considered complete. Twenty-two original prints from the third phase have been documented (Christie’s).

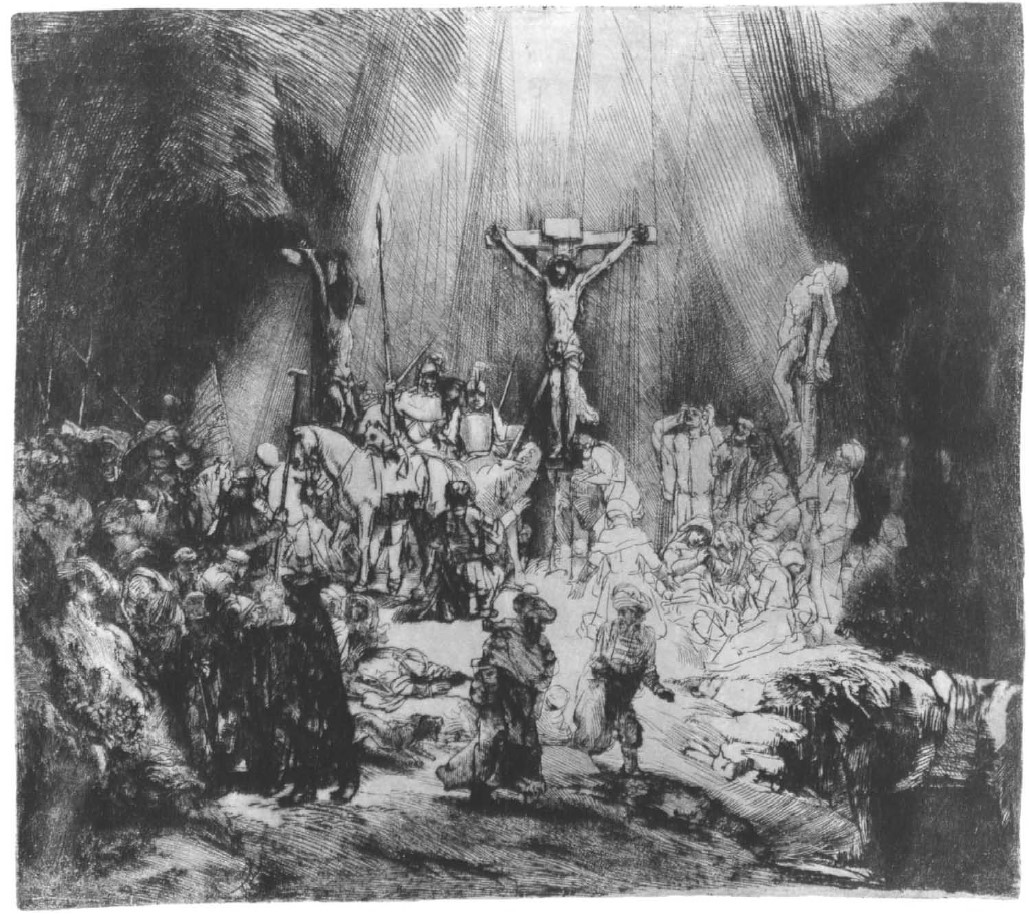

By the time the artist printed the fourth phase, some two years later, the plate detail was considerably worn. Rembrandt’s solution was to completely rework the copper surface, scraping out the bumps and smoothing the image so that only ghost lines of the previous design remained. He then engraved a new, completely different composition on top. Many of the figures have been reinterpreted or removed entirely. The appearance of Christ has been altered, large areas to the left and right of Christ have been obscured. In fact, the changes in the fourth phase are so substantial that it was long thought to have been printed from a completely different plate (Christie’s). A fifth phase was created after a local printer acquired the plate, added his own address, and made several impressions.

The third phase of Rembrandt’s “Three Crosses”, dated 1653, a contemporary print of which is offered at the auction, depicts the moment of Christ’s death and the revelation of his divine nature, which, according to the description in the Gospel of Luke, 23:44-8, occurs during “the darkness that fell upon the whole earth” (Princeton). In the even darker fourth phase, Rembrandt scraped and burnished large portions of the plate, altering some of the bystanders and changing the expression on Christ’s face so that he is now shown suffering on the cross before his death – the moment when, according to Matthew, 27: 45-46, he cries out, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?” Using burin for engraving, along with a drypoint needle, Rembrandt darkens much of the pictorial field with a piercing black rain of long oblique strokes, heightening the strong contrasts between light and dark. Huge apocalyptic shafts of light cut through the sky and fall on the crucified Christ, the emotional and compositional focus of the scene.

The context of the creation of the work

In 1653, when he created the work dedicated to Christ’s Crucifixion and death on the cross, Rembrandt was also experiencing a kind of Golgotha in his own life path. It is likely that this circumstance also contributed to the extraordinary experience, expression and impact of the artwork, as well as to its enduring fame through the ages to the present day.

In the midst of ongoing war, lawsuits and personal problems, Rembrandt produced only two dated works in 1653. By this time, he was a highly successful artist. He was in his late forties and had created more than 200 paintings. It had been a decade since he received 2,000-4,000 guilders, roughly equivalent to $250,000-750,000, to create one of his greatest masterpieces, The Night Watch (“Christie’s”).

One work, dated 1653, is his melancholy reflection on fame – “Aristotle with the Bust of Homer”. The second is an engraving – the largest, most innovative, ambitious and technically difficult print he ever undertook – “Christ Crucified between Two Thieves”, also known as “The Three Crosses”.

The great decline in Rembrandt’s artistic output in 1653 can be largely attributed to the problems that befell him. His wealthy wife had died ten years earlier and he lost the great support she had given him in all aspects of his life and work. In 1653, he is involved in litigation with his former mistress, a nurse hired to care for his son Titus after the sudden death of his wife Saskia. He was also summoned several times to the courts of Amsterdam for non-payment of taxes and for quarrels with his neighbours.

He delayed payments on the house he had bought in 1639 and began to borrow substantial sums to pay off his debts, but this only deepened his financial problems (Petev 2024: 49). Perhaps the most important event affecting the decline in artistic production was the First Anglo-Dutch War, a battle for naval supremacy between the Netherlands Republic and England that had begun the previous year and continued throughout 1653. The war put the economy of the Netherlands under enormous pressure, which in turn led to a reduction in commissions for artists.

Amid the difficulties, and perhaps driven by financial considerations, Rembrandt focused more on printmaking, experimenting with new styles and techniques. However, even this proved insufficient. He had to sell many of his etchings in order to be able to afford to print the “Three Crosses”. At the cost of a greatly reduced quantity, however, the quality of his artistic output increased enormously.

It is this great masterpiece by Rembrandt, which once became his own “Golgotha”, that is being offered to connoisseurs of fine art at our Easter auction. Of course, this is not an original print from Rembrandt’s hands and press in the 17th century, but a contemporary print. Due to the specificity of engraving as an art – the possibility to print it in more copies – and because of modern methods of copying and quality printing of the images from old engravings, the images on modern prints differ very little from the original ones, but therefore they are quite affordable. The excellent quality of the print of Rembrandt’s “The Three Crosses”, which is included in the auction, allows us to fully indulge ourselves in the communication with the world of the genius master, with his vision, experience and reflection on the eternal theme of “Golgotha”.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Bibliography:

British Museum: Британски музей: “Трите кръста” в British Museum – https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1848-0911-39 Accessed 03.04.2024

Metropolitan Museum: Метрополитън: “Трите кръста” в Metropolitan Museum – https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/354631 Accessed 03.04.2024

Petev 2024: Петев 2024: Петев, Тодор, В огледалото на Рембранд. Нов български университет, София, 2024.

Princeton Museum: Принстън: “Трите кръста” в Princeton Museum – https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/11023 Accessed 03.04.2024

Raynov 1938: Райнов 1938: Райнов, Николай. История на пластичните изкуства. Т. 9: Модерно изкуство. София, Ст. Атанасов, 1938, 48-49, цитат по Петев 2024: 47.

Christie’s: The legacy of a difficult year: Rembrandt’s Christ Crucified Between Two Thieves — also known as The Three Crosses. Christies 24. 06. 2022 – https://www.christies.com/en/stories/rembrandts-christ-crucified-between-the-two-thieves-6f3fed56ad2740258571a95c70efcc87 Accessed 03.04.2024

Hind 1912: Hind, Arthur Mayger, Rembrandt’s etchings: an essay and a catalogue, with some notes on the drawings. New York, Scribner, 1912, no. 270

Lambert: Lambert, Gisèle, Les Trois Croix. exhibition at the Bibliothèque nationale de France – https://essentiels.bnf.fr/fr/image/b5816352-fa7f-480b-b116-7daa640e23a1-trois-croix-1er-etat Accessed 03.04.2024

Ludwig 1952: Ludwig Münz, Rembrandt’s Etchings: Reproductions of the Whole Original Etched Work (London: Phaidon Press, 1952)., no. 223

Orenstein 1995: Orenstein, N.M., S. Dickey, 1995. Rembrandt’s is Prints and the Question of Attribution. Catalogue Entry N94. In: Liedtke, Walter and alii, 1995. Rembrandt Not Rembrandt in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Aspects of Connoisseurship. Vol. II. Paintings, Drawings and Prints: Art-Historical Perspectives. Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York, 1995, p. 218 etc.