“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St.

The Artistic Manifesto

Şenol Podayva’s manifesto is both a poetic and conceptual self-portrait of an artist who draws his strength from nature, memory, and a deep sense of inner truth. Although written in the language of modernity, it unfolds a philosophy intimately connected to traditional Anatolian culture and to the symbolic system of Alevi-Bektashi spirituality. It is composed in the spirit of mystical schools that perceive art as an inner path and a means of spiritual expression. For the artist, colour, nature, line, figure, and motif are not merely formal elements, but spiritual structures. They are imbued with memory, conscience, gratitude, and love for both the visible and the invisible.

According to Şenol, art is not merely a visual act but an expression of the inner perception of nature — “to look with the eyes, but to see with the soul.” This idea is carried into his understanding of the line — every brushstroke is a mark of a moral and spiritual journey. Nature (a central theme in Alevism) is the essence of being, and each trace of the brush is its breath. Nature is both teacher and studio, through which the soul travels along its spiritual path, and colour becomes a language of the heart and of intuitive knowledge.

The figures in his paintings are not realistic bodies, but shadows of memory, as if emerging from a folk song. Just as folk music preserves collective memory in Alevi tradition, so too do Şenol’s images carry its echo — alive and shared. He pays tribute to the ancient spirit of Anatolia — not as an ethnographic motif, but as a living, breathing presence.

His art is also a form of clear conscience — silent, grateful. It does not seek to persuade but to bow and to partake. The artist does not pursue fame but walks an inner path toward Truth. For him, tradition is not a thing of the past, but a breathing fabric of the present — horses, carts, stone houses and mountains come alive not as nostalgia, but as the pulse of contemporaneity.

He sees himself as a farmer of the soul — tilling his inner world and sowing colour like seed. He does not speak to the community, but becomes its inner voice, akin to the poet-singer in Alevi tradition. It is a matter of honour for the artist to carry visual motifs of the tradition across time — to keep them alive. Every line is a segment of the Path and a way for the artist to remain true to the Alevi Truth.

Abstraction in Şenol’s work is a natural outcome of spiritual maturation — a ripe fruit of intuition. It emerges from the deep bond between human, nature and colour. It is not a quest but an arrival — at the essence. And this arrival is a central notion in his art. It does not strive to describe, but to uncover that which lies beyond sight: the essential Truth.

„The Cart“

The painting „The Cart“ depicts a seemingly ordinary rural motif — a horse-drawn cart with two passengers. Yet beyond this everyday scene unfolds a profound spiritual and cultural journey, deeply rooted in Anatolian tradition and Alevi-Bektashi thought.

The composition draws the viewer into a world where nature is not a backdrop, but a living being through which the soul’s path (seyr u sülûk) passes. The mountains in the distance rise like spiritual forces, the road curves in a ritual rhythm, while the fields and sacred cypresses compose the inner movement — not only of the cart, but also of life itself. As in the artist’s manifesto, nature is the true atelier — a source of meaning, colour, and breath (nefes). The horse carries an additional layer of symbolism — a mediator between worlds, as in the Sufi tradition, where the body (the horse) serves the soul (the rider) in the journey toward Truth (Hak).

The two travellers — a man and a woman — are depicted with laconic simplicity, not as portraits but as shadows of memory, figures from a folk song or mythical recollection. The woman’s red headscarf evokes kızılbaş identity — a sign of honour, sorrow, and fidelity. In this pair, one may also recognise mythologised archetypes such as Adam and Eve, or Ali and Fatima — the revered Alevi union of wisdom and purity. In Alevi tradition, the human image is not only permitted, but also encouraged. In the tekkes (Alevi lodges), portraits of saints and spiritual guides are present — not as idols, but as bearers of memory and identity.

The artist has consciously chosen naïvist style — despite his academic training — speaks of closeness to folk visuality and of sincerity. This is a characteristic gesture in Alevi art, where symbol, colour, and emotion hold greater importance than anatomical accuracy or perspectival precision. „The Cart“ is more than a landscape — it is a visual zikr: a silent prayer, experienced with the eyes. It becomes a bridge of colour, figures, and memory to the heart of Anatolia and the Balkans.

„Steep Mountains“

In „Steep Mountains“, Podayva presents the mountain not as a landscape, but as an inner structure — a terrain of spiritual ascent, accumulation, and resistance. It radiates a sense of elevation, but also of humility and contemplation — a persistent symbol in the spiritual geography of Anatolia and the Balkans.

The mountains are formed of sharp, diagonal lines that repeat rhythmically — almost like a visual nefes, a layered song that climbs upwards. Their symmetry and stepped form recall the Sufi path (seyr u sülûk) — not as obstacles, but as stages toward Truth (hakikat). As the artist writes, “Art is not a search, but an arrival” (varış). The mountain here is not a beginning, but a destined height — a spiritual direction toward essence. In Alevi tradition, varış signifies precisely this: reaching God. The painting follows that logic — like a procession of ascents, in which each mountain is a stage along an inner path.

Nature here is majestic, yet not wild — it does not intimidate, but calms. The ridges carry the memory of stone, and the shades of blue evoke a twilight morning — a time of insight and peace. The composition is crowned by the symbolic image of a small white sun above a yellow-green sky. The landscape is a thinking subject, and the viewer is both guest and student in this scene of contemplation, where nature is a teacher, as Alevi belief holds. Yet this teacher is not gentle. The mountains here are cutting — not only in appearance, but also in touch. Just reaching out would leave one pricked. This tactile sharpness is not aggression, but a demand — for humility, for measure, for inner discipline. In this world, the hand must give up possession in order not to be wounded.

In the lower right, at the foot of the mountain, a small house appears — barely discernible, and thus even more meaningful. It is the human scale, which does not disturb the harmony of nature, but accentuates it. In Alevi tradition, the dwelling carries memory and spiritual connection — it is not possession, but manifestation. The little house is a threshold between the earthly and the beyond — an echo of dwelling that longs for peace.

Though formally calm, the canvas carries an inner tension — the rhythm of ascent is almost musical: a silent rhythm of resistance and endurance. It evokes the Balkan and Anatolian destiny, in which the mountain is not only a barrier, but also an ethical terrain — a place for memory and humility.

„Solitary House“

At first glance — a modest scene: a house, still among layers of green, blue, and violet. Yet in the stylistic language of Şenol and in line with Alevi tradition, it is more than architecture — it is a symbol of inner dwelling, of spiritual stance, of presence without power. The house is not in the centre, but slightly off to the side — a modesty that expresses the Alevi perspective of being part of the whole, not its master. In this tradition, the home is a sign of memory and transmission — not possession, but a bridge between generations, between the absent and the living. The lines of the landscape create a spacious silence in which the house does not simply stand — it listens, waits, and keeps quiet.

Here too, the artist’s manifest statement is visualised: “Art is not a search, but an arrival.” This house is not searching, nor fleeing — it has reached its place, whether in the world or in memory. It has become part of the landscape, just as halk (the people) are part of nature — not through dominance, but through inner alignment. The row of sacred cypresses by the river completes the scene of passage: guardians and witnesses between the here and the beyond. The flowers with red blossoms lend a living pulse to the foreground. The painting is reminiscent of a nefes — a spiritual song that does not impress, but commemorates.

“Solitary House” is an emblem of quiet resilience, of dwelling without noise. It is a place where life was lived, love felt, tears shed. Solitude here is not isolation, but a measure of depth. Much like the Alevi rituals in which a person turns inward, this house is an internal structure — it possesses a silence that speaks.

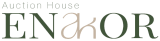

„Sunflowers in the Valley“

In this painting, Şenol Podayva abandons idyll and draws us into a dramatic, fractured landscape, where light is held hostage by darkness. Two worlds collide — the upper, crystal blue with steep peaks, and the lower — flooded in red, marked by loss, searching, and transition. On the left, three sunflowers appear — gazing at the viewer. They are not a centre, but witnesses — spiritual eyes turned not to the sun, but to meaning. In the manifesto context of Şenol’s art, they are a visualisation of intuition — an inner light, left aside from the event.

In the centre of the composition spreads a vast red stain — like memory spilling, or a wound that does not cease to bleed. Within it lies an indistinct figure, seeking its centre — at times bowed to the earth, at times poised for ascension. This is the Alevi ascetic — with a soul in prostration, in prayer, in metamorphosis. In Sufi and Bektashi context, this is the can (soul) — returning to the earth to remember where it came from.

The red is the breath of life — and of its threshold, as Şenol himself says. It is kızıl — the colour of the Kızılbaş vow, of memory and solidarity. The stain spreads toward the valley, where two or three small villages resemble sunflowers in shape and colour — as if the people are flowers from the same sun. Watching the red, the viewer almost feels it sticking to their hands — thick and palpable. Rising above all are blue mountains — waves or blades, inaccessible and unyielding. They are not a backdrop, but an archetype of unreachable peace — whether real or imagined. As often in Şenol’s work, this is a marked spiritual topography, where the forms vibrate with meaning.

The entire canvas pulses with the inner rhythm of trial. However, this rhythm does not lead to catastrophe, but to passage — seyr u sülûk. In the Alevi-Bektashi tradition, suffering is not punishment, but a stage toward varış — the arrival at Truth. Thus, the drama of Sunflowers in the Valley is a deeply human story — open to the projection of the viewer.

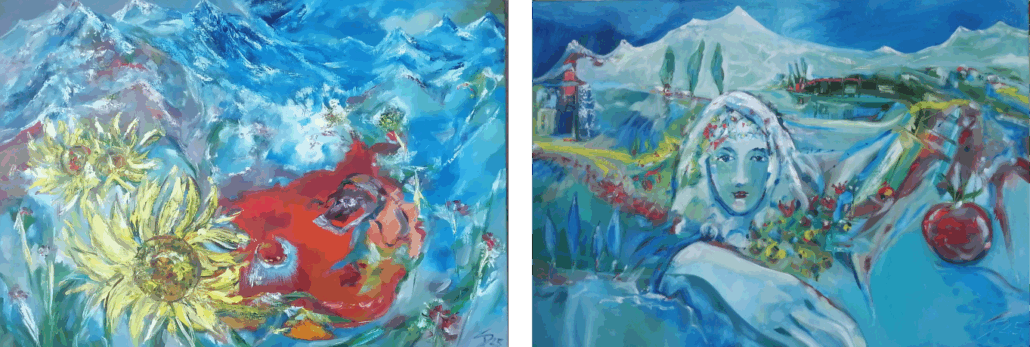

„Maiden in the Field“ (The Bride of the Mountain)

Şenol Podayva evokes an image that is both figure and spirit, land and memory. At the centre is the head of a young woman — not a portrait, but an archetype of the mountain’s bride. She embodies harmony between human and nature, generations and fertility, the hidden and the revealed. Her body is opened into the landscape — both part of it and its centre. Her hair is made of flowers; her gaze holds mountain water. Her face does not shine with sunlight, but with the memory of the women before her, whose voices echo in her dream — sometimes joyful, sometimes sorrowful, as the artist tells us. Within her are hidden the songs and tears of her foremothers — in a flower, in a fruit, in silence, as in the rituals of Alevi women, where the past is sung and whispered, but never disappears.

The mountain is not a backdrop, but the backbone of the being. The valley — with villages, houses, and trees — is not scenery, but the body of the world. Everything belongs to a living system in which the maiden is both fruit and root, and branch. To the far left — once again the sacred cypresses, guardians of memory. In the lower right — a red apple: not merely a symbol of fertility, but also the secret the maiden carries — the life entrusted to her. As often in Şenol’s work, red marks the boundaries of life and inheritance. The style is pure and expressive — there is no realism, no idealisation, but sign, metaphor, imprint of light. The colours are in a cool range — blue, green, white — with pulsing accents of red and yellow. The composition is a dream — but one in which the mountain thinks, the water remembers, and the maiden watches.

According to Şenol Podayva’s manifesto, art is varış — arrival, not search. Moreover, this painting is such an arrival — of the figure, of memory, of meaning. In the Alevi-Bektashi tradition, the feminine principle is the centre — the spiritual axis, the voice of the earth. Maiden in the Field is not a portrait, but an epiphany — a divine manifestation in human and natural form.

Şenol Podayva inscribes his art within the core themes of the exhibition, building powerful bridges between memory, nature, and spirituality. His paintings embody the idea of landscape as cultural memory — not merely depictions of environment, but inner geographies of consciousness. Through images such as the house, the mountain, the river, the female figure, and the horse, the artist creates visual-symbolic bridges that connect generations, myths, and rituals. His art is steeped in Alevi rituality, where line and colour are not formal choices, but traces of the inner path (seyr u sülûk), placing him among the artists who work with the themes of the body and memory, ritual and myth. His stylistic language brings together abstraction and fragment, symbol and intuition — a natural resonance with the thematic cores of abstraction as bridge and the fragment as bearer of the whole. The woman in his paintings is not a portrait, but an epiphany — a divine image in human form, aligning him with the theme of woman as bearer of culture. Flowers, rivers, horses, dwellings — in his work, everything is a bridge, but not between two fixed points: rather, between inner states, between the spiritual and the sensory, between the visible and the essential.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

Şenol Podayva was born in 1974 in the village of Podayva, Razgrad Province, Bulgaria. After completing his primary and secondary education at the local school “Otets Paisiy”, he emigrated with his family to Turkey in 1989. In 1995, he graduated from Kemal Hasoğlu High School in Bahçelievler.

In 1999, he completed his studies with second-degree honours in the studio of Prof. Nilay Büykişleyen at the Department of Sculpture, Faculty of Fine Arts, Marmara University. He received training in stone sculpture from senior specialist Ziyatdin Nuriyev and in metal sculpture from Prof. Tülay Baytug.

For three years, he worked as an assistant to the sculptor Necmi Murat, taking part in monument-making projects. He also assisted in joint projects of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sadık Altınok and Necmi Murat on ceramic panels and mosaics. In 2006, he attended the “Karagöz” studio of Yusuf Taktak for one year. He currently continues his artistic work in his private studio outside Istanbul.

Artistic Manifesto

“Art is looking at nature and seeing it with your soul.”

“A true line is as deep as a lifetime.”

- Nature is my studio.

The silence of the mountains, the flow of rivers, the memory of stones and the stillness of village roads… On my canvases, nature is not a mere landscape but the very fabric of existence. Every movement of the brush is the breath of the earth. - Colour is my language.

Inspired by Impressionism, I convey light, shadow and intuition through the language of emotion. For me, colours are not only what the eyes see, but also what the heart perceives. With cool blues I speak of solitude; with warm reds I tell the stories of ordinary people. - The figure is a mirror of the past.

My human figures are not specific bodies, but shadows of memory. They live as if they have stepped out of a folk song, on a village morning. My art is an homage to the ancient spirit of Anatolia. - Art is a clear conscience.

Painting, for me, is not a form of thought, but of feeling and gratitude. A work of art is not a spectacle, but an inward journey. It follows the traces of solitude, depth and simplicity. - My distance from modernity is not out of nostalgia for the past, but as a response to its lack of spirituality — its absence of meaning.

I am not against the new, but I do not draw close to that which has no roots. In my painting, tradition is not the past, but a living tissue. Carts, fields, stone houses… all breathe in the present day. - The artist is the farmer of his own soul.

He ploughs his inner world like a field and sows paint like seed. He lives in solitude, yet in harmony with nature. He does not address the multitude — but becomes its inner voice. - Drawing is the honour of painting.

Painting without drawing is a journey without a compass.

Drawing is where the eye is trained and the hand finds its way. A finely drawn line can carry more weight than the shadow of a mountain. As my teacher once said: “Drawing is the honour of visual art.” Every line that falls upon my canvas is part of that honour. - Abstraction is the ripe fruit of intuition.

As Picasso said: “There is nothing abstract at the beginning.”

Abstraction is not invented — it is born when one forms a deep connection with nature, with the human being, with line and colour.

My abstract works are the result of an inner transformation, a change that nature and feeling bring about within me. They are not a search — but an arrival. - Art is the poetry of truth.

It does not narrate reality — but reveals essential truth.

Sometimes this truth hides in a flower, sometimes in a glance, and sometimes in the core of an abstract form. Art is not built with reason, but with intuition, inspiration and soul.

Şenol Podayva, August 6th 2025