“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”, an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St., 2А

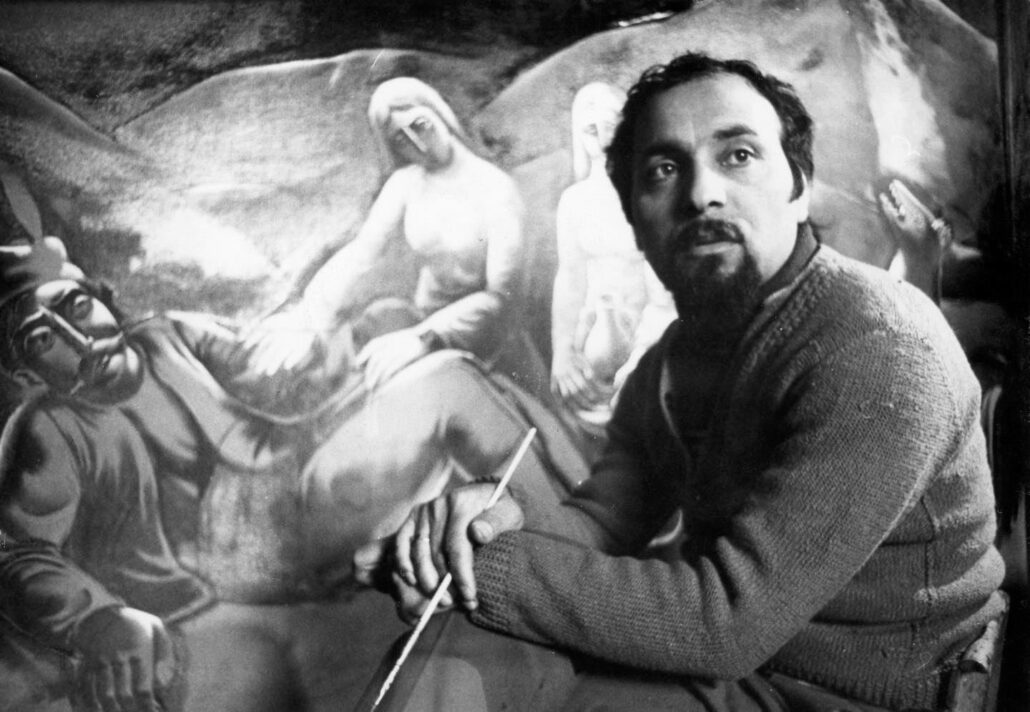

Keazim Isinov (1937–2003) was a painter who lived in harmony with the universe — quiet, gentle, immersed in deep inner experience, and entirely devoted to art. His close ones called him Kay. He grew up in the village of Sadovets — a place of ancient history and magnetic nature — where, from an early age, he developed a strong connection to the living world and to the invisible forces, he believed permeated it. His family was grounded and honourable, marked by a strong ethical culture. According to accounts by his son, Yasmin Isinov, the artist’s grandmother and great-grandmother possessed clairvoyant gifts, which may have been partially inherited by him. He dreamt — in images and visions — of scenes from the past and from eternity. One such dream involved a Gothic battle by a lake, which later proved to coincide remarkably with archaeological findings. His pantheistic sense of the world was not a philosophical concept but a form of experience — joy, faith, and devotion to the living.

From the age of twenty, Isinov practised yoga — not as an ideology, but as a way of being. He did not belong to any religious communities but held deep respect for all faiths, carrying light as an inner measure for life and art. His son recalls: “He was a person of great spiritual depth and at the same time extremely modest.” He did not seek affiliation with institutions or public recognition. Through his paintings, he wished to show that the world is bright, beautiful, and harmonious — not only dark, as it is often portrayed. He worked every day — in oil paints, with the ritual constancy of someone for whom life and art were one and the same. At times, he worked through the night, with almost no sleep — in a quiet, focused state of contemplation and effort. His wife, also a painter, was his steadfast support — in daily life and in meaning.

Isinov was a painter of light, but not in the literal sense of a landscapist — rather, in the realm beyond the visible: one who saw inner worlds. A quiet, reserved, deeply concentrated man, he created in a unique space of contemplation — between religious faith and artistic intuition. For him, the world was filled with invisible vibrations, with radiances, tremblings, and movements of matter, which he sensed and translated into the language of colour and form. The faces in his paintings are like icons. The naked body is a revelation. And his painting is like a message to the world — patient, light-bearing, and faithful to itself.

In his son’s recollections, Isinov emerges as a painter of states — not of situations, but of inner states of the spirit. He was one of those artists who did not paint what he saw, but what he experienced in visions and dreams. He believed in light as mystics do — not as a physical phenomenon, but as an ethical and sacred reality that shines from within. His paintings often appear as visions — the figure rising out of mist, out of glow, out of colour. The faces do not look at the viewer, but rather seem to listen to something beyond. In this world of radiance and contemplation, Isinov did not paint bodies — he painted their inner worlds, as if each figure were a projection of an inner voice.

“Motherhood” is an intimate oil-on-canvas composition. It depicts a woman with a head covering, holding a child in her arms, surrounded by lush vegetation, blue-tinged flowers, and a radiant aura. The colour palette is warm and saturated, with prominent golden and violet tones that emit an inner light. The figures are stylised and simplified, and the space around them is filled with symbolic elements drawn from nature. The central axis of the painting runs through the woman’s tilted head and the sleeping child. Their bodies form a closed circle that draws the viewer’s gaze inward and creates a sense of intimacy and protection. The woman’s body forms an arch — an architectural gesture of shelter, embedded in nature.

Isinov’s characteristic light dramaturgy is present. The woman and child are not illuminated by an external source; they emit light themselves. This inner light is warm, golden, and gently contrasts with the cooler background tones. The purple behind them acts as a halo — not a religious one, but an ethical and internal one. The surrounding greenery is not so much naturalistic as idealised — the leaves play an almost decorative role.

The woman does not look at the viewer, but inward — into the child, into the very act of existence. Her gesture is not only maternal, but also ritualistic. The composition resonates with an archetypal iconographic structure known across the Balkans and Asia Minor for millennia — from the Egyptian Isis with the infant Horus, through Cybele with Sabazios and Semele with the young Dionysus, to the Christian Virgin Mary with the Child. All of them are manifestations of the same primordial figure: the Mother-Goddess, bearer of life, love, and sacred wholeness. But here, there are no religious signs or markers. “Motherhood” is a secular icon of care.

This inward gaze is the key to the kindness that radiates from the painting. In this sense, it can be read as a visual archetype of kindness — an image in which touch, light, and nature merge into one. “Motherhood” thus intertwines several of the central themes of the exhibition: the senses — through the tactile softness of the figures and the leafy textures around them; the woman as a cultural mediator — not only a mother, but a composite figure of protection, connection, and harmony; and most of all — light as an ethical bridge that does not come from outside but emerges from the bodies themselves. Without any declared religious affiliation, yet with a sacred presence, this scene affirms love as the foundation of the world — not through declaration, but through radiance.

At first glance, “Toward the Heights” appears to be an abstract composition in vivid, fluid tones — orange, gold, indigo, green, and pink. However, behind the expressive colour field, a figure begins to emerge — a clearly defined anatomical body, upright, with raised arms. The form is masculine — with broad shoulders, a sculpted chest, and a taut abdominal line. The body is nude, but it radiates more inner light than physical mass — as if sculpted from light rather than matter.

In front of the chest, at heart level, a second image appears in profile — a woman’s face with a headscarf, eyes closed, hinted at in greenish-blue and violet hues. Her body is not visible; she is not solid, not part of the composition’s real-world space. She is an image embedded in the man’s heart — something intimate and internal, cherished and alive, though bodiless. She could be a mother, a beloved, living or departed — what matters is that she is carried within.

The composition is entirely vertical, the colours rising like flames. The title “Toward the Heights” does not indicate a geographical direction, but an inner, ethical one. The man is not ascending, but elevating — carrying this presence with him, with memory, faith, and love. She is not merely a recollection — she is the very core of his ethics.

In this sense, the painting is neither an abstraction nor a religious vision, but a visual ritual of the intimate. An image in which the inner person is revealed not as anatomy, but as a bearer of relation. The sensory impulse toward the heights is both a movement and a belonging — not alone, but together. The male body holds within itself an otherness — a tender centre, where love is an inward orientation.

“Sunrise” is a composition of pronounced corporeality and sensual expression. Against a smooth, darkened background, a female body takes central stage — kneeling, with arms drawn back and her face lifted upwards. The silhouette is clearly outlined, without facial features or detail, yet sculpturally defined, shaped by light and shadow in ochre, copper, and deep yellow. Behind the figure, a fiery red sun is rising — a second circular mass that both visually and symbolically balances the composition.

This body is not individualised — it has no facial traits, no gaze toward the viewer, no story. It is an image of the feminine flesh itself, of female bodily energy, captured in a moment of curve, between night and sunrise. The contours are soft yet firm, with classical purity reminiscent of ancient sculpture and fertility iconography — somewhere between Aphrodite and the Great Mother.

In “Sunrise”, the erotic is not provocation but source. It is not the erotics of seduction, but of self-radiance — the figure is alone, closed within herself, focused inward rather than toward an external object of desire. The pose also evokes ritual — kneeling, with hands and face lifted toward the sky. This transforms the erotic into the sacred. In this context, “Sunrise” may be interpreted as a painting of awakening — not only of the day, but of the body, of desire, of feminine energy. The flesh becomes the dawn of being — not as the opposite of spirit, but as its first form of manifestation. Here, eroticism is primordial, embodied, and silent.

The Bridges of Keasim

In the context of the exhibition “Sofia–Istanbul: Bridge of Art”, the work of Keazim Isinov unfolds as a form of inner bridge between ethics and aesthetics, between the human and the light. In his paintings, the senses do not merely perceive — they participate. Touch becomes a gesture of love, sight becomes a path to insight, and light becomes a bearer of inner truth. His female figures are not portraits, but embodiments of spiritual wholeness — between motherhood, eroticism, and sacred tenderness. They echo ancient archetypes without directly citing them, as if cultural memory has become bodily — not narrated, but lived through flesh and light.

In this sense, Isinov’s work resonates with several of the exhibition’s key themes: “The Senses as Bridge”, “The Body as Cultural Memory”, abstraction, “The Woman as Cultural Mediator”, “Flowers”, and “Light”. But above all, there stands one quiet, profound idea that serves as his inner compass in art — that the world is luminous, kind, and worthy of love.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

Keazim Isinov (1940–2023) was born on 16 April 1940 in the village of Sadovets, Pleven Province. He graduated from the National Secondary School of Fine Arts in 1960, and in 1968 completed a degree in painting under Professor Nenko Balkanski at the National Academy of Arts. After graduation, he worked as a restorer at the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Monuments. In 1969, he joined the Research Institute of Psychology and Neurology as an art educator. His artistic work spans painting, small-scale sculpture, sculpture proper and miniature art.

Isinov was the recipient of numerous awards both in Bulgaria and abroad. He was awarded the Order of “St. Cyril and St. Methodius” – First Class (2006), as well as the “Golden Age” Order of the Bulgarian Ministry of Culture (2015). In 2005, he received a Presidential Honour from the President of the Republic of Bulgaria, along with the special “Artist of the Year” prize at the 10th Salon of the Arts at the National Palace of Culture (NDK), where in 2010 he also won the First Prize. That same year, he was awarded the title “Artist of the Century” in the international competition “1001 Reasons to Love the Earth”, organised by the “2000” Foundation in the Netherlands.

In 2012, he received an award from the national campaign Guardian of the Traditions. Earlier in his career, he won numerous prizes in competitive exhibitions, including: Third Prize for Sava Dobroplodni (Shumen, 1971), Third Prize for Portrait of Maria Gigova (BSFS, 1973), Third Prize from the Union of Motorists (1974), Second Prize for Winged Dimo (BSFS, 1975), Second Prize in the Portrait of Sofia competition (1977), and First Prize at the International Humour and Satire Competition in Gabrovo (1977). He was also awarded a certificate of merit at the 10th Painting Biennale in Szczecin, Poland (1983).

He held solo exhibitions in Sofia, Pleven, Sevlievo, Razgrad, Blagoevgrad, Gotse Delchev, Lovech, Bursa (Turkey), Vienna (Austria), Tokyo (Japan), London (UK), as well as in Sofia’s Sredets Gallery, Art 36, Arte Gallery, Minerva Gallery, and the Vrana Palace. Among the most notable were his anniversary exhibition at the National Palace of Culture (2010), his presentation at the National Museum Earth and Man, and his first exhibition in 1971 at the Union of Bulgarian Composers.

A Story by the Artist’s Son

My father’s close friends used to call him “Kay”, while Aksinia Djurova described him as “the ecstatic pantheist”. From a very young age, he had a profound connection with nature, nurtured during his childhood in the village of Sadovets. We still maintain ties with the village—it is unforgettable for its landscape and spirit. I’ll never forget a painting called Gothic Warrior. It was a powerful work depicting a mounted warrior. He told me he had dreamt of the figure and described a battle by a lake that he had seen in his dream—he said he had taken part in it. Later, it turned out that Sadovets, his native village, had indeed been a Gothic settlement, and when specialists came to study the region, they confirmed that such a battle had really taken place. I remember being completely stunned when I found this out.

He grew up in the fields and forests, in a family of honest, grounded people. My grandfather was strict but fair, and my great-grandmother and grandmother were said to have had clairvoyant gifts. That beautiful natural harmony, the tales of times past, and the light mystery surrounding his grandmother—perhaps all of these sparked his vivid imagination and pantheistic perception of the world, which he later expressed through his art. Throughout his life, he rejoiced in and loved every leaf, branch, and animal he encountered.

He had been practising yoga since the age of twenty and continued his daily exercises until the very end. He was remarkably vigorous—at the age of 82, he could still do pull-ups on a horizontal bar. Yet he never adhered to Buddhism or Hinduism. He respected all religions, but was not bound by any single philosophy. He simply saw the world differently from most people. He experienced everything with extraordinary depth.

He was an exceptionally humble person. He never showed off, never pushed to be part of structures or societies just to gain visibility. Things seemed to happen for him naturally, as if “from above”. If he had a mission, it was to show through his art that the world is not only ugly and sorrowful, but also luminous, beautiful and harmonious. The faces in his portraits, for instance, often resemble icons.

He worked in several studios, and the paintings that our family now owns are kept in the last one he used. It was there that he completed his final painting, Eros and Psyche. I will never forget the intoxication of the smell of oil paint—it still lingers sometimes. He worked constantly. Every morning he would drink a coffee—he loved cappuccino—and go to the studio. In his later years, he suffered from insomnia and told me that he would sometimes sleep just 20 minutes at night, then get up “to do a bit of painting.” When he and my mother lived with her parents on Benkovski Street, he would even paint on the floor, and they’d have to step over him—we have a photo of that. He was incredibly strong-willed. Nearly all his works are in oil; towards the end, he also experimented with oil pastels. His formats ranged from jewelled miniatures painted under a magnifying glass to canvases two or three metres in size. As a young man, he also worked with sculpture—we still have several pieces in stone and small wooden figures.

He painted constantly, and thanks to my mother, he never had to concern himself with anything else. He was unfamiliar with domestic matters—right to the end, he had little awareness of practical things, even money. Nevertheless, he was never a bad father. My mother was the pillar of our family; she was also his manager, and perhaps even sacrificed her own artistic career so that he could fully express everything inside him. They were like communicating vessels—always together. She passed away in 2018, and although he remained composed, he clearly took it very hard.

More than once, people described him as a cosmic being—someone who did not accept the constraints and taboos of today’s world. His deepest belief was that a person could be eternal. He was a man of exceptionally high spiritual awareness and, at the same time, extraordinarily modest. He was someone who lived entirely through his art. To me, his paintings were unique messages to the world. They personally taught me to love detail, to have patience, and to remain true to myself in some quiet, enduring way. He has always been a source of inspiration to me.

Yasmin Isinov