“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St.

In Djochkoun Sami’s work, memory is not an archive but a living substance — malleable, subject to distortion and reinterpretation. His paintings lead us into spaces that seem no longer to belong to anyone: abandoned buildings, bare walls, the shadows of structures where the human is absent, yet its echo remains palpable. These are post-totalitarian remnants, stripped of ideology but not of its traces. His painting hovers between expression and figuration, marked by strong outlines, an earthy palette, and a quiet yet persistent dramaturgy. These spaces do not scream — they whisper. Objects, voids, stones and shadows gather in a horizontal time that is not chronology but sensation.

At the centre of his practice stand “time” and “memory” — “its power to return, to change, and to take new forms”. Collective memory and trauma (war, displacement, totalitarian regimes) do not appear as a ready-made narrative but as a dissolving and transforming form — “an entanglement of architectural and historical echoes” and “fading, fragmented stories”. In his words, “the long shadows of history, though invisible, continue to govern the imagination of contemporary society”.

Sami creates new modes of narrating collective memory — “drawing from the symbols of progress and decay, from the grand narratives of the past, and from the elusive, abstract nature of memory itself”. He does not illustrate history — he distils it. War, exile and oppression are transformed into symbols and fragments that refuse to remain silent. In some of his works, the political appears as grotesque, as mask, as scenography of power’s absurdity — a theatre of flags, a ritual of meaninglessness.

And yet, even when painting ruin, Sami creates structure. Even when the subject is decline, the form remains stable. Even when memory is pain, the painting becomes an effort not to forget. His works shape a gravitational field of themes — memory, ruin, withdrawal, uncertainty, and imagination under pressure. They speak of what remains when meanings collapse — and of the persistent light that continues to flicker even in the most uninhabitable spaces.

“Residence BY” presents a piece of modernist architecture overtaken by nature and by time — caught between memory and dream, between structure and decay. The architecture is made of concrete and glass — brutalist in form, but softened by vegetation. The house glows from within, as if burning with inner memory — warm, protective, almost cosy, and yet solitary, isolated, overtaken by the elements. The building resembles a relic of a former modernist utopia — one of those “new worlds” designed in the name of progress. However, here, the utopia is lonely, overgrown, consumed by nature and shaken by the storm. The light within and beneath it (reflected from below) is less electric than symbolic — a memory, a residue of life that refuses to go out. The villa becomes an image of the fragile dichotomy between the human attempt to master space and the enduring force of the natural.

The structure appears inhabitable, yet not inhabited — a house that remembers it once was a home. Its inner glow is like residual warmth from a life no longer present. The landscape around it — wild, wet, pressed by wind — suggests that the house comes from a post-human future, like an overgrown, illuminated shell of a former civilisation.

According to the artist, the painting draws the viewer into “a surreal dream in which reality feels suspended”, or perhaps into a virtual reality. The villa does not simply glow — it hovers with “ghostly weightlessness”, defying gravity and becoming an image of the “paradoxical dimensions of weight and lightness” the artist seeks. This unnatural stillness in a fractured space links directly to René Magritte’s “The Empire of Light” — cited by the artist as a key inspiration for the work. As with Magritte, here too the light is severed from time and place, creating “an unsettling experience”. But while in “The Empire of Light”, day and night coexist simultaneously, in Sami’s work the disjunction lies in weight — the structure is at once brutally physical and gravity-defying, more akin to Magritte’s The Voice of Space (1928). The artist invites the viewer into a world where the laws of physics give way to the logic of contemplation and imagination.

Anyverse carries an ironic insight — that in a globalised, technologically mediated reality, every world begins to look like every other. Therefore, memory, identity and difference become the last barriers against the disappearance of meaning.

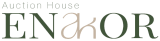

The painting depicts a female figure with her eyes and ears covered, isolated behind a scratched transparent surface. She is not a portrait, but an image of a contemporary prophetess — a figure who “sees” beyond the visible. The artist draws an allusion to the ancient oracles Cassandra and Tiresias — whose blindness signifies another kind of vision. The figure wears VR goggles, and her gestures — including the unusual position of her hand, with thumb and forefinger extended — evoke interaction with a digital interface. In this world of technologically mediated vision, reality is no longer watched — it is measured, sensed, guessed. The red and white marks on the glass may suggest traces of touch, memory, or injury — but we do not know whether they are on the outside or the inside. Thus, the boundary between body and world, between viewer and image, begins to blur. This is a universe without a centre — a virtual space where vision is replaced by speculation and prophecy becomes an attempt to measure the distance between what once was and what can never be again.

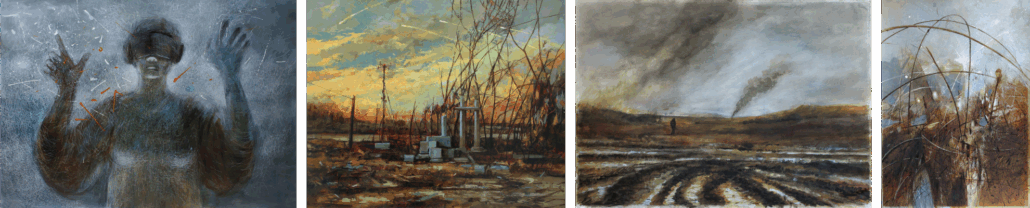

„Navigational Beacon“ is a painting of devastation that does not cry out — it glows. The landscape is desolate and wounded, with shattered ground, ancient ruins, and a cultural imprint left alone among mud, wires, and silent signals. The sky burns in dramatic yellow-orange tones, cut through by the trails of rockets or planes — luminous furrows that slice through both atmosphere and memory. The scene could belong to the past, the present or the future, to any place where the air carries traces of projectiles and the earth — of ancient civilisations. The classical ruins among which the signal mast rises speak of loss — not only of life, but also of history, meaning, and orientation. This is a painting of ruined knowledge, of the relics of a civilisation that still transmits signals, even if no one receives them anymore.

The viewer may sense something unusual in the perspective of the trees and branches: the forms are coarse, excessively large, as if the scale has expanded. This is a visual strategy of drawing the gaze into the image — inspired by a painting by Şeker Ahmet Pasha (“Woodcutter in the Forest”) and by John Berger’s essay on it. Berger observes how such “errors” in perspective do not weaken the scene, but transform it into an experience — an environment that envelops both the figure and the viewer. Thus, Djochkoun Sami enters into dialogue not only with the theme of war, but also with the visual tradition of “Western” painting in Turkey.

The painting likely also expresses solidarity with a specific wound of the contemporary world — the war in Ukraine. For many in Turkey, it is not only a geopolitical disaster, but also a personal cultural trauma. The historical ties between Turkey and Crimea — especially through the memory of the Crimean Tatars, the peninsula’s native Muslim people — make the violence there particularly painful. Crimean Tatars were expelled by the Russian Empire to Bulgarian lands and to modern-day Turkey; some of the artists in this exhibition are descended from those communities. For them, Crimea is not a distant symbol, but a lost ancestral homeland and a restless memory made raw once again. Through this sensitivity, „Navigational Beacon“ can also be read as a cry for remembrance, a call for vigilance — a beacon transmitting not only coordinates, but pain.

In a world of fragile stability, technologies shine, but their meaning is destabilised. The central object — a beacon with a red light — rises above a wide river, while in the background glimmers the silhouette of a concrete bridge, reminiscent of the infrastructure of southern Ukraine. In the foreground lie fragments of classical architecture — broken columns, supports, stones, among shrubs and bare earth. The layering of epochs — classical culture, Soviet infrastructure, contemporary mast — transforms the landscape into an archaeology of the present. It is a point of orientation, yet with no certainty that anyone still follows the signal. The red light is not merely technical: it pulses across time, trying to hold together the boundaries of the cultural world, while everything around it crumbles, erodes, declines. Perhaps this is an island of function in an ocean of meaninglessness, or it is a lighthouse of a civilisation that has not yet surrendered. On the other hand, perhaps — a call sent out into a world that no longer listens.

„Deserter“ is a landscape of abandonment — of position, of cause, of meaning. At its centre stands a solitary human figure, almost swallowed by fog and mud, turned with their back to the viewer. They hold a weapon pointed downward. Not a victor, not a victim, not a hero, not a coward. They are not walking away from horror — they are walking into it. Their back intensifies the distance — not only spatial, but also ethical. This figure refuses to belong, yet seeks neither refuge nor safety, but judgement.

The landscape is muddy and flat, ploughed through by military vehicles and footsteps. Fires or explosions are smouldering to the left and on the horizon — likely strikes on an industrial site. The devastated black soil and industrial surroundings evoke Ukraine (possibly the Donetsk region) — tormented by an unprovoked war. It is a territory where war is felt in the air, the earth, and in the gait of the one who refuses to be part of it. This is not a scene of battle, but of withdrawal. The sky is low, the smoke drifts like a wound. Everything is stripped down: earth, sky, smoke, human. However, in that simplicity lies an ethics of refusal. The figure does not attack, does not defend — they leave. The direction of movement is unsettling: the deserter walks back towards the front. Perhaps this is not escape, but a doomed choice. Perhaps a final gesture — of atonement or of understanding. Some leave with their bodies, others with their hearts, and still others walk towards it in order to renounce it forever.

There is no answer as to whether the soldier is Russian or Ukrainian. That is precisely the universality — the figure could be any soldier, at a moment of extremity, caught between order and conscience. „Deserter“ is not an accusation but an act of compassion. Not an act of fear, but of intolerability. It marks the boundary beyond which a person refuses to be a weapon.

„Planetarium“ is not a dome of knowledge, but a sphere of disintegrated orientation. The thin arcs bending across the composition evoke celestial trajectories — traces of technological orbits and the rigour of astronomical instruments. Yet nothing here functions — neither as science, nor as vision. The space is fractured, as if not only the planetarium had been struck, but also the sky itself had suffered an explosion. This is not a place where stars are aligned — it is where the projection has been interrupted, torn, forgotten. If this painting bears the scars of war, it is a war against imagination itself. The instruments of knowledge are uncalibrated, the coordinates — lost. Once, there was a vision of the universe here; now, only its distorted memory remains.

The lines — at times distinct, at times barely perceptible — trace an impossible geometry. They diverge, repel, and create a sense of residual balance that threatens to collapse at any moment. This is not architecture, but an epilogue. As if, someone began building a sphere to organise the world — but instead of a cosmos, ended up with a cacophony. Instead of a star chart — a scattered system of signs, reminding us that even the pursuit of knowledge is not beyond the reach of destruction. This is not an image of the universe, but of a world lost in its own sky.

On a personal level, „Planetarium“ carries the memory of childhood wonder — the Varna planetarium, once a home of dreams, now appears as an abandoned set from another time. Yet behind this sentimental memory lies a philosophical layer, inspired by Peter Sloterdijk: just as the Earth was once perceived as the centre of a divinely ordered cosmos, so too in totalitarian Bulgaria the world was presented as predetermined by socialism and the determinism of class struggle. After Copernicus, humanity lost that central perspective and found itself in an infinite space without a fixed orientation. The image of the planetarium becomes not only a symbol of scientific shift, but also a metaphor for cultural disorientation — where knowledge and dream were subjected to ideological control, and then abandoned.

Djochkoun Sami’s artworks fit into the exhibition’s concept as a quiet, profound axis — they do not build bridges through gesture, but raise them from shadows, memories, and withdrawal. His art does not shout identity — it contemplates it in its dissolution. Rather than connecting through a visible thread, it sends out an elusive impulse between cultural memory and contemporary dislocation. Through architecture, ruin, the ethics of refusal, and imagination on the edge, Sami traces fragile bridges between past and present, between trauma and the effort to go on — even when meanings fall apart. At times, these bridges pass through new technologies — virtual reality, digital interfaces, and contemporary navigation systems appear not as symbols of progress, but as markers of a new sensitivity in art.

In his work, painting and architecture intertwine to follow the fragments of memory that refuse to disappear. For him, memory is not accumulation, but movement — “a power to return, to change, and to take new forms”. It moves through trauma — wars, displacements, regimes — and yet retains its capacity to be a bridge. In its deepest layers, another truth emerges: that even war can be a bridge, but not towards victory or reconciliation — towards non-being. Sami’s art whispers this through broken geometry, exposed landscapes, bodies and spaces that remember, but cannot return. In that whisper lies its deepest message: that every connection between cultures, people, and times is also a question of fragile vulnerability.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

Djochkoun Sami was born in 1973 in Silistra, Bulgaria, and lives and works in Istanbul. He received his BFA in 2004 and MFA in 2011 from the Faculty of Painting at Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts in Istanbul. His works have been featured in numerous group exhibitions across various countries, as well as in illustrated magazines, poetry books, and theatre posters. He has held solo exhibitions in Istanbul, Ankara, Silistra, and London.

Sami’s painting inhabits the threshold between expression and figuration, intertwining architectural and historical echoes with the compositional discipline of formalist painting. Using a restrained, earthy palette and a process grounded in drawing, he builds surfaces in which line and form sharpen into clarity. Abandoned buildings from the recent past often serve as a starting point — stripped of their original context and politics, they become anonymous, depoliticised spaces. The play of light and shadow lends these places a quiet drama, as objects, stones, organic fragments, and voids share the same painterly stage within a horizontally unfolding sense of time.

Stories behind the works

At the centre of his practice stands memory — its power to return, to change, and to take new forms. His work is shaped by an awareness of collective traumas: war, displacement, and the burden of totalitarian regimes, echoing certain currents in postwar European painting. Through his engagement with fading or fragmented histories, Sami reflects on the contradictions of the modernist project and explores collective memory as a form of narration — one that draws from the symbols of progress and decline, from the grand narratives of the past, and from the elusive, abstract nature of memory itself.

In some of his works, the political appears in its grotesque mask: struggles for power reduced to theatre, flags raised in empty ritual, dreams traded as commodities. Through these images, Sami quietly examines how the present remains shaped by the long shadows of history — shadows which, though invisible, continue to govern the imagination of contemporary society.

Djochkoun Sami