“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St., 2А

Woman, Music and Cultural Memory

The art of Aynur Kaplan is a world where woman is not merely a subject, but a source of light, a centre of creation, both image and expression. Each of her figures carries not only personal emotion but also collective memory—especially that of the Balkan woman, marked by forced displacement, loss, and nostalgia. “I always leave half of the face in shadow— that is the fate of the uprooted. That’s how I paint myself,” the artist shares. Behind the decorative opulence of her canvases lies a deep, silent inner story—both personal and collective. In Kaplan’s work, woman is a quiet heroine of forced migration, of memory, and of inner rhythm. She is not simply a joyful presence, but a bearer of time, culture and pain— contemplative, yet infused by movement and sound.

At the heart of this world lies music. Aynur Kaplan is an artist with pronounced musical-visual synaesthesia—she experiences music not only as sound, but also as colour, form and image. Her paintings do not illustrate songs; they recreate them in hues, waves, lines and rhythmic elements that envelop the figures and build visual compositions with acoustic and melodic resonance. As she herself puts it: “When I listen to music, especially the Bulgarian songs from my youth, I see colours and shapes. And the other way round—when I paint, music starts playing in my head.” Her experience—of painting and music simultaneously arising—goes beyond synaesthesia and enters the realm of ideasthesia: not just a sensory-emotional interweaving, but a visual recreation of multiple characteristics of music.

Her work weaves together poetry, ancient myths and beliefs, ritual signs and symbols, and elements drawn from the ornamental traditions of the Balkans and the Middle East. In this hybrid visual language—where the Balkans meet Anatolia, where European symbols intertwine with oriental textiles—Kaplan’s figures build a temple to the inner world of the Balkan woman, intimate and universal at once. They gather the voices of lost places, the memories of communities, and the rhythms of a world which, even as it vanishes, transforms. The woman in these paintings is a mediator—between sound and form, between past and present, between the silence of pain and the vividness of experience.

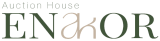

In the composition „Letter“, the entire space vibrates like a field of music. The background behind the woman is fragmented into passages of colour and rhythmic gestures that describe not a room, but a resonant inner space. The red and ochre arcs around her head swirl like melodic currents. To the right, verticals in blue-green and violet hues resemble keys—visual equivalents of music, of what is heard and felt. Her hair lifts in the invisible wind of a sound wave that has passed through her entire body. The flowers in the vase on the table are rhythmic patches—like melodic accents that mark an emotional motif. Everything in the composition sustains this sense of rhythm and synaesthetic harmony, in which the woman not only hears music but lives within it.

Within this world saturated by sound and colour, the letter in her hands stands out as silence—a white envelope containing the echoes of the past. It is both a musical rest and a vessel of nostalgia—the only element without colour, without motion, yet imbued with profound inner meaning. Half the face is cast in shadow—a hallmark of Aynur’s work, which, in her words, reflects both the pain of forced displacement and the presence of memory. The letter is not merely a symbol. It is a reflection of a pain that must not be sung, yet must be preserved. In its colourlessness and silence, it gathers the sounds of absence—the songs no longer heard, the places no longer inhabited. It is a white silence in which memory still resounds.

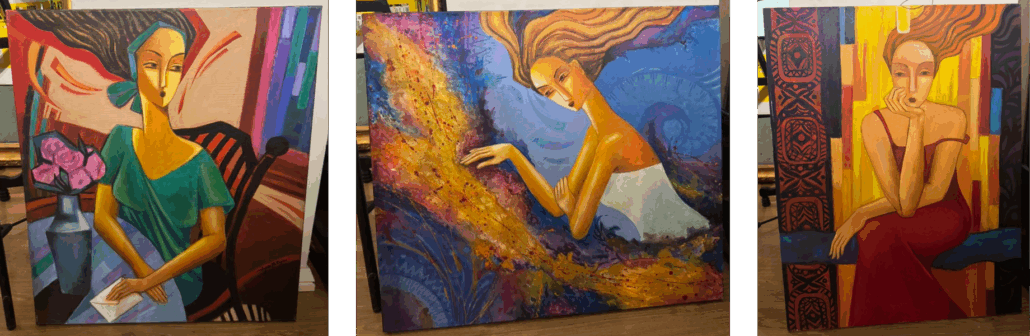

In “Music beneath the Fingers”, the woman seems to be leaning on a golden-violet river of music flowing before her. Her outstretched right hand touches the diagonal stream of melody, which pours over a decorative, inky-violet sun in the lower left corner. The gesture is not one of control, but of response and curiosity. The woman leans into the melody as one would lean on something familiar and alive, coming to know it through touch. The contours of her body are clearly outlined against the background, and both the woman and the flowing melody share the same golden tonal range, in contrast with the blue-violet environment. Her hair, lifted upward, unfurls in waves resembling strings or sound lines, while the blue background behind her vibrates in smooth spirals—a visual equivalent of a sound wave, not only in the ear, but also in space.

Here, music is rendered as a tangible presence: it flows before the woman as a melody that is not only audible but also palpable—alive, dense, and full of motion. In Aynur Kaplan’s world, sound has texture and weight—it can be touched, even gently gathered with the fingers, like water, silk, or a memory. The woman is not absorbed by it, but senses it through her body—through skin, palm, elbows. This is not an illustration of music, but a representation of nonverbal communication in which vision, bodily perception and melody fuse into a single experience.

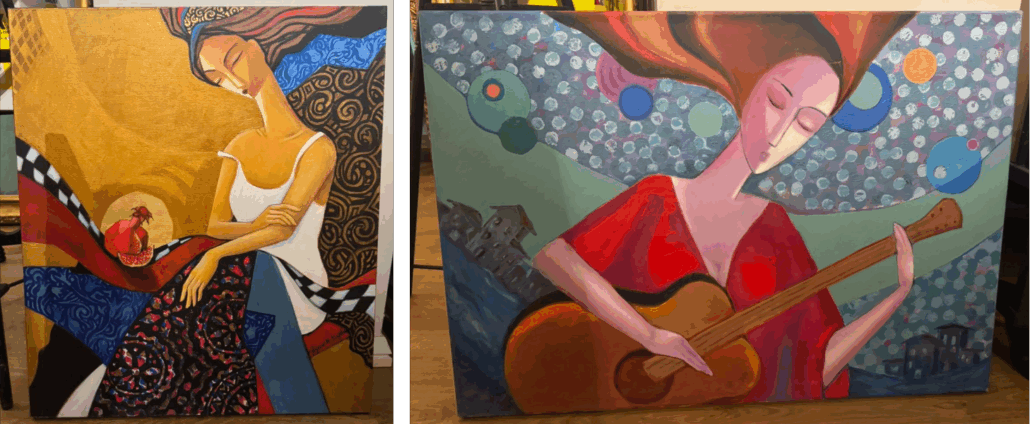

In “Suspended Note”, the female figure sits on a dark blue bench, with lips pressed together, eyes narrowed and gaze fixed. Her hair coils upwards in copper-orange waves, as if lifted by wind or submerged in water. Her right hand supports her head, forming a vertical line, while the left arm hangs down diagonally—the body remains still, yet the surrounding lines suggest movement. The background is made up of bright vertical blocks of yellow, ochre, terracotta and red, arranged like a panel mosaic. Among them, a yellow rectangular shape cuts across her hair, interrupting its natural contour—a surreal element that seems to “pin” the figure to the background. On either side of the composition, ornamental vertical strips recall woven friezes or rugs, framing the image like a stage set.

This is a composition of restrained tension and theatrical threat, expressed through a refined visual language. The figure radiates self-control and resolve, yet beneath the surface flicker traces of anger and a measured erotic charge: in the narrowed eyes, in the strap fallen from her shoulder, in the way she looks—and does not look—at the viewer. The woman simultaneously asserts, warns, sets boundaries and tempts. The title “Suspended Note” carries a dual meaning. One is the diplomatic note: silent, but charged with steely tension. The other is the musical sign. Her hair, rising like a double stave, suggests that even here the female figure is bound to music—though mostly embedded in the decorative background. The combination is unusual: jazzy geometric rhythms in dialogue with oriental textile motifs hint at an ethno-jazz performance with a seductive edge. The suspended note is neither subdued nor forgotten—it seduces to be sung by a voice worthy of its tension.

In “The Sacred Pomegranate” a female figure is seated on a bench within an architectural space crowned by a gilded dome, whose silhouette evokes Byzantine churches transformed into mosques — layers of memory from the Balkans and Anatolia. Her head is bowed, eyes closed and hands crossed; she is inward, contemplative. Her hair rises in a stave-like five-line formation, as in other works from the series, but here the uplift has a spiritual charge — a visualisation of liturgical singing. She is dressed in a simple white summer dress, while around her and in her lap ripple numerous textiles decorated with motifs drawn from ancient royal cultures: Mycenaean, Byzantine and Ottoman. Upon a broad red cloth with a chequered band lies a split pomegranate crowned with a great corona, its blood‑red seeds revealed. In the golden wall behind it, a circle of light surrounds the fruit like an ancient Egyptian solar disk or a saint’s halo.

This is a composition with a liturgical resonance in which every element points to a ritual of veneration: the woman’s posture, the fruit’s central placement, the gilded halo. Yet there is a subtle play: the young woman is not in ceremonial vestments but in contemporary dress; the deity is not a distant other but a sensuous fruit. She does not present the pomegranate as an offering — the pomegranate itself is the sacred centre before which she stands in concentrated reverence.

Across multiple cultural layers the pomegranate bears meanings of love and blood, of life and sacrifice. In ancient Greece, the ritual tasting of pomegranate marked the conjugal rite; in myth it was Persephone’s taste of the fruit that bound her to the Underworld. In later Christian readings, the pomegranate signals resurrection; in Islam it signifies abundance and vitality. In relation to femininity, the pomegranate often signifies fertility, corporeality and the mystery of motherhood. Kaplan offers a contemporary interpretation here: the pomegranate combines pleasure, sensuality, traditional knowledge, wealth and sovereignty.

The gilding, the domed vault and the woven historical layers convert the composition into a temple of cultural memory: the past does not act as mere backdrop but as an active presence. The fruit fixes the presence of memory and the spatial, bodily and temporal inheritance it carries. The woman, in modern dress, stands both within and outside this ritual: on the one hand a guardian of memory and tradition; on the other hand a mediator between the echo of the dome and the genetic memory of the seeds — between the earthly and the sacred, the bodily and the spiritual.

In “The Cosmogony of Eurydice” we see a young woman with half‑closed eyes playing a classical guitar. Her head tilts gently towards the instrument; her face is composed and calm, her body curved in a soft motion. Her hair streams upward and sideways across a cosmic field of planets, moons, stars and abstract celestial bodies. Behind her, urban silhouettes of buildings unfurl into nocturnal depths.

The title plays with the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus — the poet whose music shapes worlds and crosses the border between life and death. Here the roles are reversed. Eurydice is the holder of the famed instrument: she is the musical demiurge and does not wait to be rescued, but creates. Myth and present fuse in her image: ancient fate and modern autonomy meet. She is no longer the object of masculine gaze and effort but the subject of creation — the author of a cosmogony.

This is not a portrait of a woman who merely plays — it is the portrait of a woman who gives birth to universes. Her hair floats into the heavens she conjures; her voice is movement, her body a conductor of rhythmic energy. The landscape behind her is not a mere backdrop but an effect — the earthly realm emerges from the chord she strikes. In this painting, Eurydice does not flee the subterranean; she transforms darkness into poetry and music, constructing realities through the force of her own thought, sensitivity and contemplation.

The Bridges of Aynur

In the exhibition “Sofia–Istanbul: a bridge of art”, Aynur Kaplan lays her vivid bricks into many bridges. First and foremost, her case powerfully illustrates the art-therapeutic function of art—the ability to heal trauma, to overcome forced displacement, loss of homeland, and nostalgia. Secondly, Kaplan’s work centres on the theme of woman. In her paintings, the female figure is simultaneously creator, icon and mediator—a bearer of culture, bodily memory, rhythm and contemplation. Each painting weaves together senses and perceptions: vision, hearing, taste, touch, and inner bodily awareness. It fuses cultures and arts: music takes on image, image follows musical structure, and poetry arranges itself in visual rhythms. It interlaces epochs and traditions: layers of ethnocultural textile ornaments, rituals and mythological references form both a cultural memory of the body and a memory of place—both of which move through time. Through her musical-visual language, Aynur Kaplan builds bridges between ethnic and religious traditions, between the local and the universal, between the personally lived and the collectively-historically shared. In her artistic world, the ritual is a bridge, the myth is a bridge, the woman is a bridge—an expressive, communicating presence that unites shadow and light, the erotic and the spiritual, the root and the flight.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

Aynur Mahmudova Kaplan was born in 1964 in Momchilgrad, Bulgaria. Following the forced migration of 1989, she settled in Izmir, Turkey. For ten years, she received private training from one of the doyens of contemporary Turkish art, Şeref Bigalı, and in 1996, with his encouragement and his introductory remarks, she held her first solo exhibition. Since then, her artistic path has continued uninterrupted—she has organised 27 solo exhibitions and participated in over 100 group exhibitions in Turkey and abroad.

She has received several awards, and her works are held in public and private collections both in Turkey and internationally. She is a member of the Union of Turkish Painters and Sculptors.

In addition to her personal artistic practice, Kaplan is also known as an international art manager. She introduced to Turkey the tradition, common in former socialist countries, of organising artistic gatherings, through her project Artists’ Encounters. From 2009 to the present day, she has curated 35 international art meetings held in both Bulgaria and Turkey. She has also extended this project to Cyprus and has played a significant role in the promotion and recognition of contemporary Turkish art, both domestically and internationally.

She has participated in exhibitions and symposia in Germany, Poland, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, Croatia, Bosnia, Romania, Italy, and Russia. She has served on jury panels and has presented academic papers and lectures at symposia.

She speaks four languages and is also known for her poetry. She has published two poetry collections, and her translations have also appeared in print.

In her artworks, the woman is often a central theme. She works in contemporary painting, using oil and acrylic techniques, and employs stylisation as a key artistic approach. She works actively in her own studio.

Stories Behind the Works

The woman is the central theme in my paintings—not only as a subject of interpretation, but also in my activities beyond art. I am deeply concerned with women’s social issues. I have founded several women’s associations in Izmir and other cities. I paint the Balkan woman. I always leave half of the face in shadow. The shadow marks the fate of the uprooted, which has always weighed heavily on me—I paint myself. I love my homeland, and I constantly long for the place where I was born. I began painting—and writing poetry—as a way to express my nostalgia for home. I have published two collections of poetry, and a third is forthcoming. Nostalgia is the central theme of my poems as well.

Poetry and music are the sources of inspiration for my paintings—especially music. There is always music playing at home, especially in my studio. I paint to the songs of my youth—Bulgarian pop music, also Vysotsky, and others. Music evokes in me the images, shapes, colours, and rhythms of the paintings, especially when it comes to the background. Moreover, the reverse is also true—the paintings bring music to my mind. I love to sing.

Aynur Kaplan