“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St., 2А

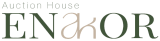

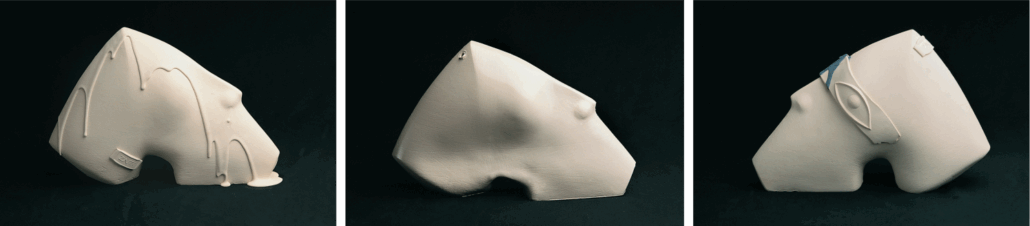

Ziyatin Nuriev’s masks are part of the 2000 project INTERVENTIONS, consisting of 99 sculptures made of industrial faience, all based on the same base form. Most of them retain the natural white colour of the material, while around 25 have been treated using the raku technique – a firing process in an oxygen-free environment – which gives them graphite and charcoal tones. The project draws on the structural logic of musical composition, transposed into sculptural material: 99 variations on a single theme. Each mask functions like a phrase, a variation, a modulation – a slight deviation from the base form, achieved through an addition, a subtraction, or a gesture that alters the intonation without disrupting the whole. This is a composition built on a logic akin to that of classical music: not improvisation, but a deliberate development of theme through form. In this way, the project acquires not only visual presence, but also rhythm – a volume that is almost acoustic.

According to Nuriev, the project INTERVENTIONS is a philosophical parable about the human tendency to intervene. Each mask is an intervention upon the same form — sometimes minimal (removals, additions), other times more radical (deformations, cuts, incisions). Not because it is necessary, but because humans want to change things — the form, the material, the body, the world, themselves. Even when there is no reason, they will find one. “There doesn’t need to be a reason — and even if there isn’t one, we can come up with 99 reasons to intervene. For example, there’s no strict reason why this project should have 99 pieces, but I could give you 99 reasons why it does”, says the artist.

In the masks shown in the exhibition, intervention is not destruction, but creation; not aggression, but participation; not correction, but a gesture of empathetic engagement with matter. Other masks from the project involve more drastic interventions. Yet in both types of alteration, the very essence of the human relationship to the world becomes visible: not to contemplate nature, but to interfere with it; to transform it into something new; to create an artefact, an image, a new world. In this sense, INTERVENTIONS is a demonstration of the essential act of culture-making — the fabrication of the artificial, imagined human world, which is distinct from the natural one, even though it emerges from it.

Nuriev’s masks do not conceal identity — they create it. Created from the very earth, from the white material in which the beyond seems to have left its imprint. This is not the white of emptiness, but of memory — of something that was once alive and is now only a trace, yet something that could be again. The sculptures present a fragment of the human: a silhouette marked by a nose — a sign of a face, of breath-life, of the emotion of scent that gives rise to memory; of smell, through which we understand before we see or hear. The masks affect the viewer on a deeply sensory level — not only tactile, through the hand (with the fine and gentle smoothness characteristic of Nuriev’s surfaces), but also visually, through the eyes, through the mind’s eye, through the sense of smell, and through an inner bodily sensitivity that recalls things it has not yet experienced in this world.

Demiurgic Interventions

Each mask is an intervention — an act upon the body and its form. These interventions are not limited to the surface; they reach into the very shape of nature itself: a creamy liquid splashed from above and trailing in fine streams, a veil pulled tightly around the face, eyes placed on an eye bandage, with blue seeping through it like blood. These gestures do not wound the form — they complete it. They are not ornament, but gesture — the final one, the one that gives the body meaning, not merely flesh. The eyes on the bandage do not look — they guard. With their stylised shape, they recall ancient Egyptian images — not as symbols, but as signs left behind by a civilisation that knew other ways of seeing. This is not vision, but memory. It is recollection in the Socratic sense — of the divine world that the soul once beheld before birth, and now recognises again through images.

These sculptures are not portraits, but outlined essences — fragments of bodies, sculpted with the refined sensitivity to the fragment that distinctly characterises Nuriev’s artistic language. Their world is one of metamorphosis: a state of transition and transformation — from animal to human, from body to object, from nature to culture, from naked and vulnerable to protected. Within them, minimalist silhouettes intertwine — a human knee and a face, a fragment of a leg and the head of a horse, armour, the past, and perhaps the future (they “look” upwards). The knee fragment may also be perceived as the outline of a horse’s head. This is not symbolic, but a morphological slippage — a place where a modern centaur emerges: androgynous, zoo-anthropomorphic, or trans-biological creature.

The horse’s head in these sculptures may evoke the white horse from Socrates’ chariot — the one that pulls the soul upward, towards the divine, towards the contemplation of ideas. The project also includes black masks that are not part of the exhibition but belong to the same sculptural system. They intensify the sense of duality, counterpoint, and inversion. In them, there is weight, unruliness, depth. They may be associated with the black horse from Plato’s allegory — the one that pulls the soul downward, towards the corporeal, the earthly, the fleshly.

In the geometrically stylised volumes and lines, in the reduction of form typical of Nuriev’s work, there is almost always an undercurrent of eroticism — though never aggressive or literal. In addition, the sense of smell, which these masks so powerfully mark through the nose, is the sense most closely linked to erotic attraction in both animal and human evolution. This minimalist, veiled, intellectualised eroticism carries the same impulse Socrates speaks of — Eros, the force that lifts the soul towards what it once contemplated and guides it towards the recollection of the divine. In this Eros, the masculine and the feminine are not divided but intertwined in a single body — as in Socrates’ myth of the androgynes, so too in Nuriev’s sculptures.

Even when reduced to fragments, these bodies carry another layer of memory — cultural-historical and archetypal. Within them echoes something more ancient — not preserved through tradition, but imprinted in the body itself. Without imitation, Ziyatin Nuriev’s sculptures evoke this memory: of ancient armour, of ritual masks, of the protective goddess whose face adorns the greaves of Thracian rulers, both kings and queens. The sculptures can also be associated with Thracian royal ceremonial helmets, on the foreheads of which eyes are depicted. These eyes do not merely indicate the inner vision of the ruler’s wisdom; they also serve to protect him, like an embedded amulet of knowledge within the silver or gold sheet of the helmet. The forms in these works resemble stylised anatomy that transitions into artefact — reminiscent of ancient Thracian greaves and helmets. The beings within the masks — sometimes feminine, sometimes masculine, sometimes beyond the human — do not look, speak or hear, but they are vividly present, and they guard.

Ziyatin’s masks do not conceal a face, do not perform a role, and do not take part in a celebration. They are neither theatrical nor carnivalesque. They resemble the ancient funerary masks of the Eastern Mediterranean — not as traces of death, but as moulds for another, otherworldly, future identity. There is no portrait in them, yet there is memory — of bodies, of the forms of possible beings, of a life not lived but imaginable. These are not beings born of flesh, but entities created by culture — possible essences beyond the biological, in which art models its own future, artificial forms of life. A human knee, a horse’s head, a face with a nose and breath, but no gaze, no listening, no speaking — this is an unusual vision of a post-human creature, sealed in white earth, sculpted in elegantly flowing silhouettes, forms and volumes, turned toward the sky. Like an ancient demiurge, Ziyatin Nuriev shapes his otherworldly future beings as a musical composition of variations on a theme, played through terracotta — as interwoven bridges within a fourfold coordinate system of past–future and imagined–physical reality.

Ziyatin’s Bridges

The horse’s head, which appears as a vision within the masks, is not merely an anatomical fragment, but a morphological key to another layer of the exhibition — the image of the horse as a bridge. It is not a figurative representation, but a reference to an archetype: the Thracian horse and rider, Socrates’ white and black horses pulling the chariot of the human soul, the Sufi Buraq of the ascension. In Nuriev’s sculptures, this image is abstracted to a silhouette, to an inner form that weaves in the idea of movement between worlds — from body to spirit, from human to the beyond, from earth to contemplation. In this way, Ziyatin becomes part of a thread in which the horse is a mediator — not through hooves, but through essence, galloping along metaphor rather than road.

For Nuriev, the fragment is not a remnant, but an essence. His masks and bodily sculptures do not point to a former whole, but to what may yet be. They do not present a face, but a possible essence — future, metamorphic, post-human. If in Pavlina Kopano’s work the fragment is an imprint of something past, in Ziyatin’s it is a mould of what is to come. Here, the fragment emerges not as memory, but as proposal. In this sense, his sculptures are not only bridges to the past, but to the imagined future — a possible world in which the body will take a new form, memory will carry a different scent, and culture will inhabit another flesh.

Ziyatin Nuriev thinks through the sense of smell not as a theme, but as a structure. His masks engage the nose not only visually, but also conceptually. This is the olfaction of form — a sense for memory, for Eros, for the invisible, for the possible. The nose in his sculptures is not an anatomical detail, but a portal to what one recognises before seeing or hearing — an entry into cultural archaeology and inner recognition. In this sense, his masks are bridges to memory, not only cultural but also corporeal — imprinted in the body before the emergence of language. In a world dominated by sight, Ziyatin reminds us that the deepest bridges pass through what we do not see, but remember with the body. Here, olfaction becomes metaphysical. It elevates matter into memory and returns it as a premonition of a future being. It is the quietest of the senses, yet the deepest — and in this exhibition, it is Ziyatin who brings it into remarkable focus.

Nuriev’s sculptures are like fragmented bodies of the future — sensory, sentient, metamorphic. They do not simply represent but evoke sensation — of touch, of breath, of bodily memory and vision beyond the eyes. In this sense, his masks are bridges between the human and the beyond, between earth and consciousness, between the antiquity of ritual and the possible futures of art. They carry the scent of cultural memory, the olfaction of Eros, the smoothness of hidden intuition and the structure of musical accord. This is not merely a visual experience, but a feast of senses, perceptions and thought — a banquet in which each element speaks its own language, yet all together form a shared figure of meaning.

In the context of the exhibition “Sofia–Istanbul: A Bridge of Art”, Ziyatin Nuriev’s masks trace out one of the most powerful bridges — between matter and idea, between body and intellect, between clay and thought. In his sculptures, the senses are not illustrative but essential — olfaction and touch shape not only forms but meanings. They are bridges through which memory passes from bodily to cultural, from past to future. His work with the fragment is especially significant: here, the fragment is not a remnant but a promise, a first cell of something yet to come. His forms move along the threshold between the natural and the cultural — clay transformed through gesture, thought and ritual. In this, one of the core themes of the exhibition emerges: culture as a bridge toward nature — not through domination, but through shared transformation.

His abstraction does not erase corporeality — it gathers it into energetic cores: concentrated images that contain Thracian antiquity, religious and philosophical traditions, the pulse of the present, and the seeds of the future. The horse appears not as a subject, but as a formal sign bearing deep memory — the Thracian horseman, the horses of Socrates-Plato’s chariot, and Islamic spirituality meet in a symbolic field that unites the local and the universal. In addition, the feminine presence — fluid, intuitive, erotic — is not separate from the masculine. The two forces intertwine in an androgynous equilibrium, where Eros is a force of creation, not of division.

In this multilayered world, ritual is not a reconstruction, but an inner rhythm that moves the form — as it did in antiquity, and as it does today. The masks, the kneepads, the movements of the body — all are fragments of living practices, carried forward into the future. Ziyatin Nuriev’s art connects modes of being in which idea and form are inseparable, and are a pathway toward meaning. From this perspective, his masks may also be read as images of future deities — not reconstructions of lost beliefs, but premonitions of a new sacrality. They arise from a forefeeling of a possible evolution, in which the corporeal and the intellectual, the natural and the artificial will meet in a new and beautiful synthesis. Such masks do not conceal a face — they reveal potential. They are the faces of ideas not yet spoken, and of beings we have not yet become.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

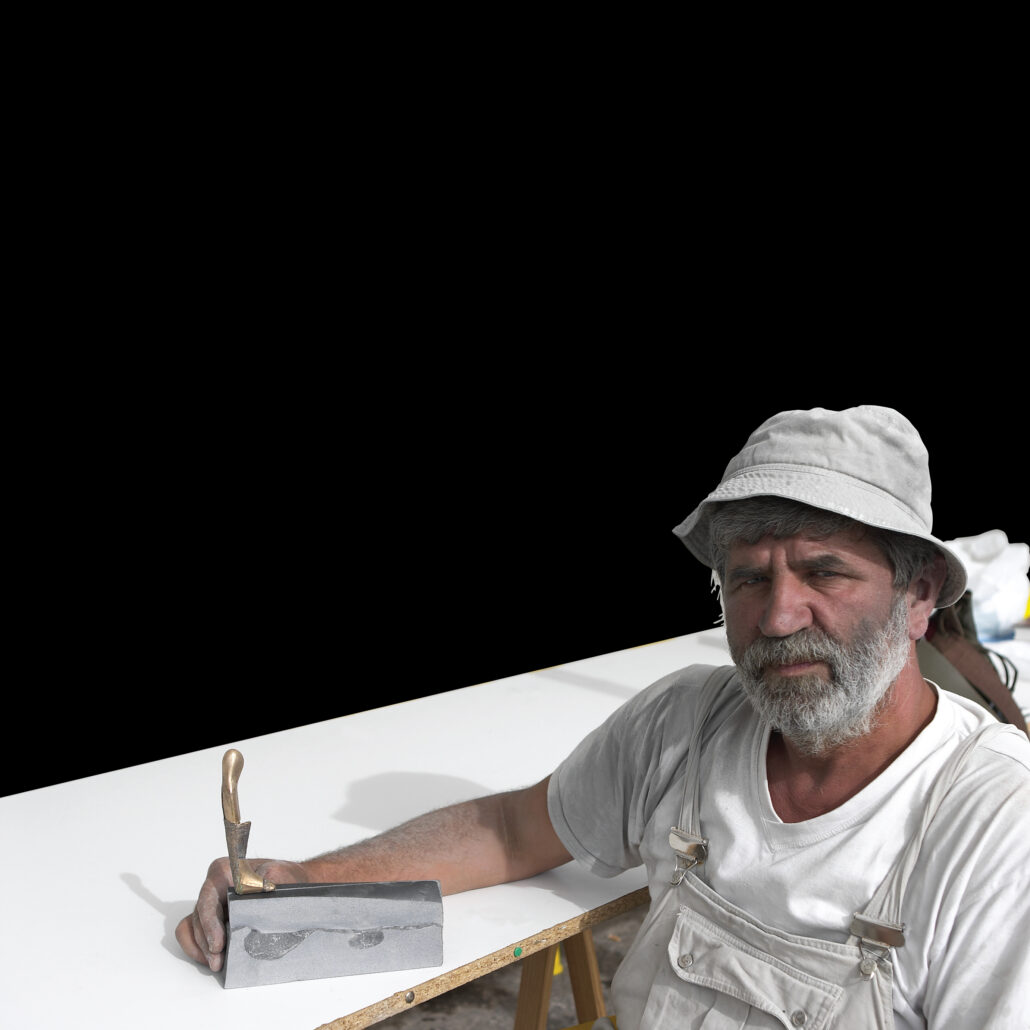

Ziyatin Nuriev was born on 8 May 1955 in the village of Most, Kardzhali District, Bulgaria. In 1974, he graduated from the National School of Fine Arts in Kazanlak, and in 1982 – from the National Academy of Arts in Sofia.

His professional career began immediately after graduation: just one week later, he participated with two works in the National Youth Exhibition in Sofia. Both pieces were acquired – one by the Varna City Art Gallery and the other by the Sofia City Art Gallery. In the same year, he won the grand prize at the prestigious International Sculpture Symposium in Otmanli (Rosenets Park), Burgas.

Until 1992, he worked as an independent artist in Bulgaria.

In 1991, he visited Istanbul for the first time as a tourist. It was summer, and all galleries were closed. While walking down a boulevard near a shopping centre, a friend accompanying him mentioned that there might be a gallery inside. The facade bore the sign “VAKKO”. Inside, everything was dazzling and opulent. After viewing the exhibition on the second floor, they introduced themselves to the gallery manager and handed her a modest black-and-white leaflet that Nuriev had thoughtfully brought along. After glancing through just a few pages, she immediately offered him an exhibition. It turned out to be the most renowned and respected gallery in Turkey.

That same year, Nuriev held his first solo exhibition at Vakko in Ankara (at the time, Vakko operated a network of three galleries – in Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir). As a result of this exhibition, he was invited to teach sculpture at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Marmara University in Istanbul, where he went on to establish the stone sculpture studio.

Since 1992, Ziyatin Nuriev has been living and working in Istanbul, actively teaching and developing his own artistic practice.

His works are held in numerous museum and private collections in Bulgaria and internationally.

Story Behind the Works

A PARABLE IN TERRACOTTA

My works in the exhibition are part of the project INTERVENTIONS, which consists of 99 terracotta (industrial faience) masks, created in the year 2000. They don’t have individual titles – they share one collective name: INTERVENTIONS. The project is a kind of parable about a deep-seated trait in human psychology – our tendency to intervene, in everything and anything, for better or worse, whether needed or not. We don’t necessarily require a reason. And even if no reason exists, we are capable of inventing 99 justifications for getting involved. For example, it was never essential for this project to have exactly 99 pieces – but I could easily give you 99 reasons why there are precisely that many.

The sculptural concept is based on a single recurring base form, onto which subtractions, additions, deformations, and various interventions are applied – visualising the very act of interference.

As for a particularly memorable incident tied to one of the works, I can’t recall one right now that would fill half a page. But I do hope that, if not all, then at least most of my pieces are the result of meaningful moments and lived experiences.

Still, I can say a few words about how the project came into being. I’m not sure how long the idea had been turning in my mind, but in the year 2000 it crystallised, and I decided to realise it. One of the key contributors to this was the renowned Turkish ceramics manufacturer VİTRA, who had set up a fully equipped studio for artists, sculptors, and ceramicists – providing unlimited materials, tools, and technical assistance.

At the time, some of my colleagues were persistently encouraging me to pursue a PhD and enter academic life, but I wasn’t keen. After I completed the INTERVENTIONS project, I thought: “Why not base my PhD on this work?” That’s how I decided on the topic: THE REPETITIVE ELEMENT AS AN EXPRESSIVE TOOL IN ART.

Since the defence of a PhD in the arts requires both a written thesis and an exhibition, I told them I would exhibit the masks. However, they replied that I couldn’t – because the works had been created before the doctoral process began. In the end, it turned out to be a case of “every cloud has a silver lining.” I went on to develop a second project based on the same concept – it consisted of twelve two-metre-tall figures and was titled THE TWELVE APOSTLES.

Ziyatin Nuriev