“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St., 2А

Kamber Kamber does not paint objects, but pulses of life: “I don’t paint what I see, but my impressions of what I have seen.” He does not describe the world but evokes it through sound, memory, and colour, like an ancient storyteller who knows no boundaries of genre. His art weaves together multiple layers of memory – from the rhythm of Rhodopean ornaments to the echoes of Thracian antiquity, which inspires him with its visual aesthetics, imagery, and stories: “I have a great interest in archaeology; the culture and art of the Thracians draw me in deeply.” This memory also encompasses a wide range of artistic forms – music, poetry, theatre, ballet, opera, cinema, modern dance, and folklore – which inspire him and often emerge in the themes and rhythms of his paintings.

In Kamber Kamber’s paintings, fabric comes before form. It is no coincidence that the first colours to strike him as a child were those woven into the rugs and carpets made by his mother and grandmother. That is where rhythm lies, where painting first begins — in the repeating tones, arranged in order and counterpoint, like notes across a stave. This primal sense of aesthetics flows into his compositions, where painting is structured like fabric, like music, like poetry.

From his own words, we can infer a synaesthetic process, in which sound is experienced as a chromatic necessity: “My greatest inspiration comes from beautiful music. I always listen to music when I paint. In harmony with the music, I detach from the earthly space and expand into the universe. It feels as if the music suggests the colours to me. I am pulled by emotions when I paint. For a while, the melodies live inside me, and then they become vibrant colours on the canvas. By the third session, the painting is still abstract — and only then do musical instruments and women emerge, performing the beautiful music.”

On the other hand, this feeling, this inner drive, is an ideasthetic impulse. It gives birth to musical colour, forms, movement and image, without a preliminary plan or conceptual sketch.. Music is not a backdrop, but a driving force. Through it, Kamber hears colours and sees sound. And if one listens closely to his paintings, one might hear the instruments he loves — the bagpipe, jazz, classical music, or the kavals of Theodosii Spassov. One might even catch the songs of the Rhodopean nightingales. Every brushstroke is a response to an inner resonance.

Form as memory, image as kinship

Artists often paint their childhood — it is a shared experience — but for Kamber it also serves as an aesthetic matrix. The image of the goat, for instance, is neither symbol nor allegory, because it is his goat, the one that lived with him, fed him, and was part of his everyday being. In this sense, the forms he paints — landscapes, female figures, animals — are recovered bodies of memory. They are stylised and geometrised, but emotionally sharpened. They do not follow academic realism but the inner logic of experience. The colours are not naturalistic but emotionally musical. The perspective is not geometric but associative.

Woman as world and bridge

In Kamber Kamber’s world, woman is the centre of human order. She is not merely a subject but the ontological frame of existence. “Everything in this world begins with woman, because she is our mother, sister, wife, the one who continues life and the human race.” His Rhodopean woman is one and the same, regardless of whether she believes in Christ or in Mohammed. In this figure, the most delicate and natural bridge is formed — between religions, ethnicities, customs and faiths. Not as a political message, but as the inherent nature of art itself. The woman in his paintings is beautiful, radiant, expressive, mythic. She is not only a source of inspiration — she embodies life in its entirety. That is why the artist says: “Woman is our world, and we, the men, exist within it.”

Landscape as cosmos

Kamber does not paint the Rhodope Mountain, but the world of the Rhodopе. He calls himself a “Rhodopeist” — not humorously or stylistically, but as a statement of belonging. “I am a descendant of this mountain, and it is my greatest love,” he says. That is why the Rhodope in his canvases is not a concrete place but a universe of colours, nature, voices, clay memories, autumn stalls, fabrics, prayers and love. The landscape is not a backdrop; it is a medium of existence. It is not depicted but evoked.

Paintings as testament

Kamber Kamber does not send curators catalogues or lists of works. Instead, he sends photographs of the backs of his canvases — and this is not accidental. There, on the reverse, where one finds the artist’s name, title, size and technique, there is something more: a trace of the hand, of the gesture, of the truth invested in the act. His art is a confession. It is music, fabric, poetry, affection and memory. It moves us because it is authentic — like the goat from his childhood, the voice from the Rhodope, the first colours in a woven rug, or music made visible in colour and form.

“Rhodopa Autumn”

In this painting, autumn is movement. The colours flow — heavy and stirring, like a Rhodopa melody. Kamber constructs the composition with a strongly marked dual structure, reminiscent of a bagpipe with two chanters, of two facing hills, or of two intertwined figures opening towards the viewer. Everything maintains rhythm and symmetry without exact mirroring, as in a traditional woven rug — almost identical, yet never the same.

The central element, a long, curved stroke of violet and white, acts as a bridge, as the neck of a musical instrument, as the outline of an animal’s horn or even a woman’s spine. It gives the composition a bodily presence and a sense of motion, not only visual but also tactile — almost like a sound one could touch. One can feel the relief, the weight of the paint, the trace of brush and knife.

The palette — deep reds, terracottas, ochres, pinks and violets — vibrates like a bagpipe. This is not autumn in the sense of nature, but autumn as memory: of woven cloth, of soil, of recollection. The dark brown background does not confine the colours but holds their strength, like a night that preserves the warmth of the day. Most striking are the black elliptical strokes with vertical stripes, reminiscent at once of windows, eyes and lattices. They may be read as signs of human presence, or of memory sealed within matter. “Rhodopa Autumn” cannot be narrated — it must be listened to with the eyes.

“Jazz”

In this painting, Kamber does not depict music — he builds it. The colours, forms and movements do not follow a predetermined plan but unfold like an improvisation, each element entering into rhythm with the next, as voices do in a jazz ensemble. The lines are not merely decorative; they carry sound. The brushstrokes are not only painterly; they are timbral.

The central male figure holds a trumpet, yet it is not drawn realistically. His face and half-closed, absorbed eyes are only sketched, and the instrument almost dissolves into the background. The musician is not separate from the space around him but merges with it, as though his body were a resonating chamber within the field of the score.

Contrasting strokes and saturated tones create a sense of rhythmic syncopation. The yellow bands cut through the composition like high notes, while the darker zones provide the depth of a bass foundation. The structure is sonic: each colour harmonises with the others, guided not only by visual logic but also by inner hearing. The painting is not a story about jazz; it is jazz itself — polyphonic, energetic, open and free. It improvises between hand and paint, resonates between viewer and sound, and continues to play long after the eyes have moved away.

“Melody”

In this painting, music is not performed but experienced. The woman does not play; she listens — inwardly, within herself. Her gaze does not meet the world but turns back into her body and her thought. The left eye is large, open, dark violet, seeing. The right is smaller, unfinished, lost in shadow, as if it does not look outwards, but inwards, towards another, more distant and intimate world. The instrument — a viola or violin — is not an object of action but of feeling. The woman embraces it, yet her fingers do not touch the strings; they remain suspended in the air, as if the very act of contact were too powerful to be realised. Here, music becomes an idea, an ideasthetic experience in which form itself turns into a harmony of sounds.

The figure carries elements of Cubism: the face is constructed from geometric segments and planes of colour. The hair is built from ribbons, almost like fabric — a multilayered thought concealed beneath red and violet hues. Even the background speaks in shapes — angles, arches, triangles, squares, rectangles. The composition creates a musical experience through mathematical form. “Melody” is not merely a title but a working method: layer upon layer, colour upon thought, sensation upon line. It is not a portrait but a story of how sound is born before it is heard.

“Touch”

In “Touch”, Kamber Kamber stages the motif of a “painting within a painting”. On the inner canvas, there is a female portrait — a young, graceful, elegant woman with an elongated oval face and short straight hair made of colourful ribbons. She is the same woman from “Melody”. She extends her hand, stepping out of the pictorial space towards something physically real, something that does not belong to the realm of painting — the viola, an object with tangible weight and substance. This is the moment when the painting wishes to cross into the world of humans, when the image strives to be more than an image — to sound.

Thus, Kamber creates a composition of transition between worlds: between the fiction of painting and the truth of sound. The female figure is not merely portrayed; she reaches for something that does not belong to her yet calls to her. That something is music — real, resonant, living music. Here, it is not painted but desired. “Touch” is a painting about the longing of the image to become sound, about the effort of painting to step beyond its frame and begin to play.

„Дует“

“Duet”

In this painting, Kamber composes not merely a scene with musicians but the embodiment of creative dual breathing — between poetry and prose, imagination and clarity, the play of colour and the logic of form. The two figures, feminine in character and drawn in a manner reminiscent of Picasso, with separated heads and interlaced bodies holding instruments, form an inseparable ensemble in which each complements and reveals the other. Their faces are like masks delineating essences.

The left figure plays the viola, her head inclined towards the instrument. Smaller and more lyrical, she carries the language of poetry — with its elusive transitions, broken verses and intuitive motion. The right figure holds a cello. She is prose: deep, solid, bearing the weight and steadiness of thought, her head upright and unmoving. Both are dressed in a multicoloured, geometric, ornamental rhythm that follows not the logic of realism but the inner melody of the ideas from which they are composed. Many arts are intertwined here.

The palette — saturated violet, ochre, crimson, ash and gold — creates a sense of vibrating inner space in which sound turns into form and form becomes sign. Kamber gives the impression that the painting does not merely depict music, but that it sounds from within, as if it were a score for the eyes. “Duet” is the final chord of the series, yet also an open portal in which the viewer may recognise themselves as listener, co-author or participant. For this duet is not only between two women, but between two principles — contemplation and expression, abstraction and substance, imagination and language.

The Melody of Bridges

Kamber Kamber transforms his Rhodopa roots into a universal language of human sensitivity. The melodic quality of the Rhodopa in his work is not merely sonic or ethnographic — it becomes a vessel of shared experience: of tenderness, empathy, and sensory harmony. Through his open, local, bodily and musical experience of the world, his paintings cross boundaries between ethnicities, cultures and religions, detaching from their native ground. For Kamber, the local is not isolation, but origin — a spring from which something universally recognisable flows.

Kamber Kamber embodies hearing as a sense and music as an art form, that become a bridge between experience and image. In his paintings, sound is visible and colour can be heard — not as metaphor, but as the genuine inner logic of perception. His paintings experience music in the same way people experience the other — whether person, culture or world — through openness, resonance and attunement. This is why, in Kamber’s work, art is not merely a personal act but a collective voice, a bridge between ethnicities, religions, senses and layers of culture, all interwoven in the melody of a profoundly Rhodopian human presence and message.

Within this melody, multiple themes from the exhibition’s concept come together and intertwine: the entanglement of senses, perceptions and art forms; memory across time, space and body; the bridge between the local and the universal; the fragment and abstraction as aesthetic strategies; woman as mediator; landscape as inner world. Through paintings in which we hear colour and touch sound, Kamber Kamber does not merely take part in the exhibition — he gives it tone, timbre and pulse.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

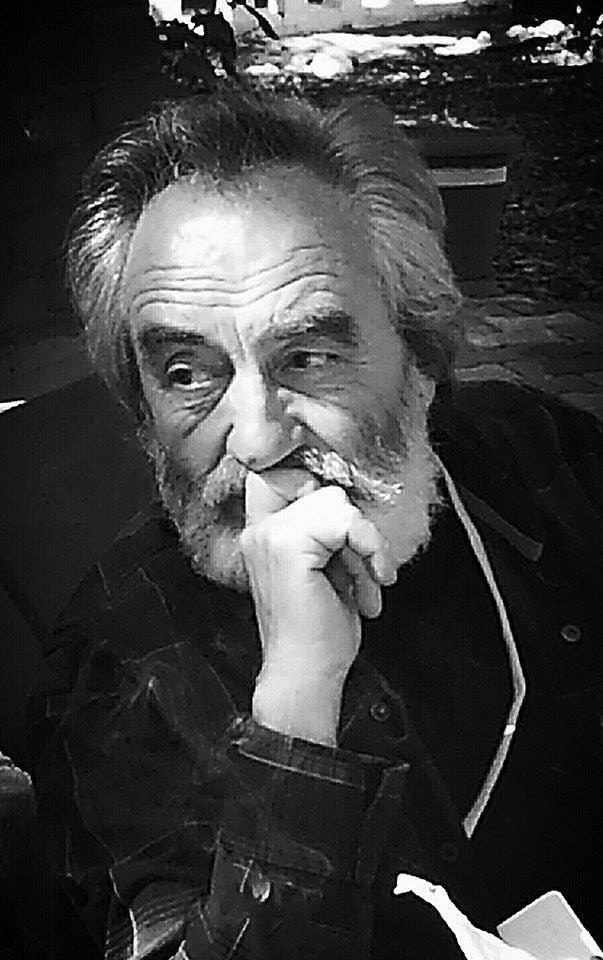

Biography of the artist

Kamber Kamber was born in 1950 in the village of Sedefche, in the municipality of Momchilgrad, in the Kardzhali region. He studied painting in Sofia between 1972 and 1977, having developed a passion for art from early childhood. He lives and works in his studio in the Momchilgrad area.

He has held around 40 solo exhibitions, including 12 abroad, and has taken part in numerous national and international exhibitions, biennials and symposiums. He has received awards from various competitions. His works are held in both private and public collections in Bulgaria and abroad.

He is the author of books on Turkish artists in Bulgaria and the Balkans.

Kamber decided to become an artist as a child. He recalls being first struck by vivid colours when he saw the rugs and carpets woven by his mother and grandmother. At the age of five, he began painting on biscuit and Turkish delight boxes — “because times were poor and paper was scarce”. As a child, he was deeply impressed by everything around him: autumn fairs with swings and stalls, the natural world, and the first successful portraits he drew were of his primary school teacher in Sedefche. At the age of ten, he began modelling clay figures of animals and arranging them by the roadside in his village. He dug the clay himself from a deposit near Sedefche. These were his first solo exhibitions, which attracted passing travellers.

After completing his military service, Kamber lived and worked in Gabrovo, where he became close friends with the local artist Nikifor Balabanov, from whom he learned much about the fundamentals of painting. After a brief stay there, he returned to his native region. He worked as a librarian and teacher, and from 1974 took charge of the municipal studio for artistic decoration in Momchilgrad.

His first proper solo exhibition was in 1972 at the community centre in the village of Zvezdel. This was followed by participation in national exhibitions. His talent was recognised, and he was selected — along with other young artists from across the country — to take part in a four-year course run by the Committee for Culture, with lecturers from the National Academy of Arts.

This was a formative period in which he painted intensively, read everything he could find about his favourite artists — Vladimir Dimitrov–The Master, Bencho Obreshkov, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Rembrandt — visited galleries, and followed with keen interest everything that came “from the brush” of Genko Genkov and Dimitar Kazakov–Neron.

Stories from the Artist

Story No. 1

I am a Rhodopa-ist. I paint the Rhodopa Mountain and its world because I am a descendant of this mountain, and it is my greatest love. I also paint women, because woman is our world, and we, the men, exist within it. In most of my paintings, you’ll find the figure of a woman, a Rhodopa woman, because to me, a woman is something sacred — she is a daughter, a mother, a wife, a beloved. For me, the Rhodopa woman is one and the same, whether she believes in Christ or in Mohammed. Her face can be found nowhere else in the world. It radiates a kindness that comes from the mountain itself.

Sometimes a single glance from a woman, a simple gesture or a chance encounter is enough to inspire me to start painting. Woman carries the deepest responsibility for the spirit of the home, for the children. She is stronger than man and less prone to despair — because she gives life and bears its great responsibility. Everything in this world begins with woman: she is our mother, our sister, our wife, the one who carries life forward. That’s why she is present in my paintings — beautiful, unique, hard-working, radiant, pure as a drop of dew.

I never stop reading. I love reading fiction, reviews, and often poetry in the evenings. When I was in the army, I read the biographies of all the great painters. An artist doesn’t need a diploma, but training is essential — that four-year course with lecturers from the Art Academy gave me refinement. It taught me the subtleties of the craft.

I can’t paint without inspiration, or on commission. I may have an idea, but I never know in advance what figures will appear on the canvas. Sometimes I finish a painting in four or five days; sometimes it takes me months. It’s hard to explain, but suddenly the feeling arises that the painting is complete. I never know how long I’ll need to finish it. And if the artist misses that moment and keeps working, the painting loses its character, its feeling, its spirit.

I find inspiration in the Rhodopa, because the mountain gives me a sense of life. After a walk in the mountains, I feel energised, and the painting almost seems to paint itself. There is something magical there — a kind of enchantment. In the mountain, I am freed from all negatives, all worries, and when I return to the studio, I pour everything onto the canvas, to the sound of good music. It feels as if the music suggests the colours to me. My feelings pull me as I paint.

Whenever I paint, I always listen to music. I have never stood before the easel with a fixed idea of what I will paint. It is the feeling that pulls me — and that feeling is often shaped by the music I am listening to at the time. I love Irish bagpipes, the violin, jazz, and the kaval of Theodosii Spassov — it lifts me from the ground and makes me fly. I love any beautiful music, except for “chalga”. In the evenings, I often read poetry. Music, poetry and painting are three sisters who cannot live without one another. That’s why, when I pick up the brush, there is always music playing.

Artists often paint their childhood. In my paintings, a goat often appears. But it’s not just any goat — it’s our goat. When I was in the fifth grade, my father bought one. I grazed her for four years; she fed us. Her image has stayed with me to this day, whenever I stand before the easel.

Story No. 2

Since my native village of Sedefche is only five kilometres from the Zvezdel Mine near Momchilgrad, I used to travel there every week on a bus full of workers — miners. Between 1975 and 1990, I created quite a few paintings on mining themes and industrial landscapes.

The people of the Rhodopa were mostly engaged in tobacco farming. I painted a number of works on this subject, especially featuring tobacco workers. Around 1990, the mine was shut down, and the labour-intensive tobacco fields also disappeared. In the urban environment, there were many cultural events, and I began to turn to other themes — music, theatre, ballet, opera, cinema, modern dance, folklore, traditional crafts, ancient art, cultural heritage, architectural monuments, archaeology, ethnography, myths and legends. All of this nourished and inspired me.

Whenever possible, I have always tried to be among poets, writers, actors, musicians, painters, sculptors, architects and others. My greatest inspiration comes from beautiful music — of any kind, except for “chalga”. The melodies stay with me for a while, and then they turn into vibrant colours on the canvas.

I never sit in front of the easel with a preconceived idea for a painting. When the muse arrives, I switch on the radio and start applying the first patches of colour randomly across the canvas. In harmony with the music, I detach from the earthly plane and expand into the universe. It is a kind of transformation — into another realm, where a battle is waged between the artist and the canvas. I am drawn by feeling, by lived emotion, and by the positive impressions left by cultural events or a conversation with someone dear. By the third painting session, the image is still abstract — and then, gradually, musical instruments and women appear, performing the beautiful music.

I have a strong interest in archaeology. The culture and art of the Thracians fascinate me deeply. Twenty-seven years ago, I created a series of paintings on the theme of Orpheus and Eurydice. One of them tormented me for seven or eight months. No matter what I did, it just wouldn’t come together. At last, I decided to destroy it. I took black paint and, with pain in my soul, began to cover the surface. After a while, I looked — and the painting had come to life. I carefully finished the process with some final retouching. In 2001, that very painting was the first one to be sold from the exhibition in Sofia.

My greatest inspiration comes from the melodies of nightingales and other birds in nature. The sound of the living world and the artist must always be in harmony. That is where everything begins. I don’t paint what I see — I paint my impressions of what I’ve seen.

Kamber Kamber