“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St.

Şevket Sönmez is a conceptual artist whose work falls within the field of metamodernism — that generation of artists who view painting not only as image, but as a site of collision between opposing values, ethics, memory, and perception. His paintings bring together references to art history, fragments from personal and collective archives, traces of mass culture, and visual residues of contemporary catastrophes — technological, ideological, and ecological. Sönmez creates spaces of visual sublimation, where individual sensitivity enters into critical dialogue with systems of image production, constructing scenes of doubt, trauma, and intellectual resistance.

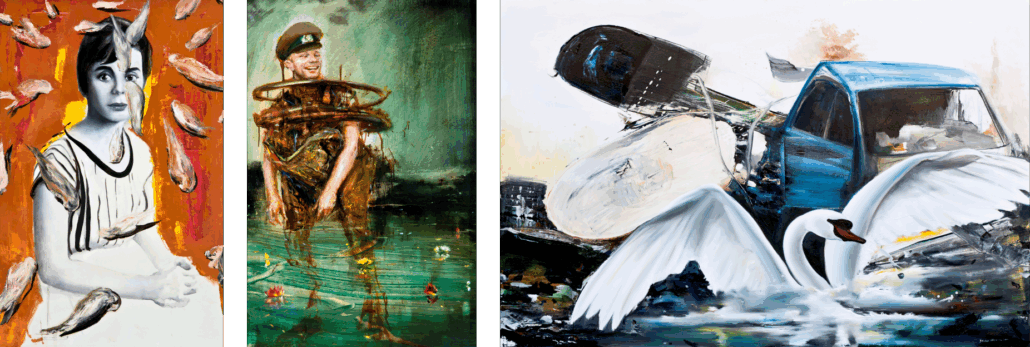

In „Portrait with Dead Birds“, against a backdrop of unsettling orange light streaked with yellow and pink flashes, we see a black-and-white image of a seated young woman. Her face is rendered with masterful draughtsmanship and photographic precision — frozen, calm, and almost emotionless, like a frame from an old television screen. She seems to be looking ahead — but not seeing. Her figure is incomplete. Her hands are only hinted at, the dress beneath them roughly sketched. The image appears like an unfinished canvas or poster — fixed on the wall of another time. She does not take part in what is happening; she is being looked at.

In the foreground, dozens of birds are falling. Not upwards, but down. They plummet — dead or dying, with drooping heads and folded wings. They do not touch the woman — they fall between her and us. The canvas is a stage, but the birds are life. That life ends before our eyes. The birds are painted expressively, vividly, materially. The woman — cold, detached, silent. As if the world were collapsing in front of an old image from the past. And she cannot move.

In the reality of large cities, such scenes are common. In early autumn, migratory birds frequently crash into the glass facades of skyscrapers — disoriented by the reflections. By morning, the ground around these buildings is often covered with their bodies. During holidays, when fireworks explode in the sky for hours on end, the stress kills even more of them, and again they fall from the sky. In this way, the modern urban environment — with its facades and fireworks — kills thousands of birds, without even knowing it does so.

In „Yuri Gagarin in the Jurassic Park Selection Process“, we initially see a kindly smiling young man in a military cap — we easily recognise Yuri Gagarin. He stands in water with water lilies, enveloped in a greenish haze and oily painterly density. However, something is wrong. His body appears dissolved, partly sunken, and his lower half resembles a plucked, flightless bird — something between an ostrich and an emu. His form is disintegrating, melting into the swamp. On his shoulders, he spins hoops — rusty, absurd, like remnants of old utopias, shackles of socialist ideology. This image of a former hero carries humour, irony, and a touch of absurdity. Once a symbol of human aspiration and transcendence, Gagarin here becomes a character in a comic book of decay — slightly surreal, slightly ridiculous. The dream of progress, once reaching toward the stars, is now bogged down in the marsh — faltering, damp, smiling from a background of vanished belief. Meaning has been erased — from the face, as from history.

In „The Swan and the Lorry“, the scene resembles a frame from a film or a dream after a crash — a blue lorry plunges into water, landing on a white swan. Wings outstretched in a desperate attempt to fly away, the swan has already been struck — almost submerged. It is the moment when machine crushes living body. The swan is rendered almost sculpturally, retaining its dignity in the midst of catastrophe — like a visual epic, tinged with irony. The bird, a symbol of the sublime, finds itself beneath the dirty wheels of the human world. From a visual standpoint, this is the anti-Botticelli, the anti-“Birth of Venus” — here, water does not give rise to beauty, but explodes in collision and kills. There is something cinematic in this post-Romantic myth — the swan of death, and of absurdity. In this work, the bird does not connect worlds, as it does in the paintings of other artists in the exhibition. The meanings have been erased.

Şevket Sönmez occupies a specific place in the exhibition — not as a builder of bridges, but as an artist who shows where and how bridges break, how meanings are erased. In his paintings, the bird — a universal symbol of freedom, flight, and hope — becomes a sign of rupture, trauma, and impossibility. It does not fly, but falls; it does not connect, but is crushed. Through this image, Sönmez reminds us that not every attempt to build a connection ends in success — and that art can function not only as a path, but also as a diagnosis of the failure to generate meaning.

As the artist himself writes: “Amidst the noise, the process of meaningful understanding becomes elusive, and what emerges as a possible explanation for today’s lived experience is a vast, incomprehensible network… In this way, individual experience fades into the fog of uncertainty, and we become oversaturated with messages — soon we may find ourselves excluded, without ever knowing why it happened to us. Today, artists engage with concepts and phenomena that are immense, complex, and often beyond the human scale of comprehension. Faced with the deeply interconnected phenomena shaping contemporary existence, a fundamental question arises: How can art — and painting in particular — reflect these complex problems?”

And the answer is: it is truly difficult to represent the very inability to understand — especially through one of the most powerful tools for generating meaning: art. Sönmez succeeds in representing, through painting, one of the eternal human dramas, from the beginning of our existence to today — that a vast part of us are not capable of creating meaning.

Through his metamodernist, post-ironic, and sometimes absurd paintings, he introduces the voice of a sceptical, mocking consciousness — one that does not seek consolation, but insists on seeing the crack in the very idea of unity — in what is perhaps the most human of qualities: the ability to create meaning. His works are a visual counterpoint to hope, a reminder that bridges are not a given, but rather a fragile intellectual construction, easily dismantled.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

Şevket Sönmez is born in 1978 in Plovdiv, currently living in Turkey. He completed both his MA and PhD at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in Istanbul, and has also lived in Paris.

His works navigate a space between the influences of past artistic periods and contemporary cultural phenomena. His compositions, anchored in the visual memory of art history and at times directly referencing well-known masterpieces, remain unmistakably modern due to the forms and figures that inhabit them. While the compositions draw from the rich fabric of art history, Sönmez’s iconographic cycle is firmly rooted in the present. He uses his archive as a basis for constructing enigmatic, figurative, and semi-abstract compositions. The interplay between historical references and contemporary imagery generates a layered visual narrative that alludes to both personal and collective memory.

In today’s image-saturated culture, Sönmez continually confronts the imposition of images shaped by certain “parallel” structures. These structures, perceiving themselves as superior to individual identities, tend to become encapsulated — a phenomenon that may be described as a process of “fetishisation”. Sönmez’s artistic practice may be characterised as a determined resistance to this process. Drawing inspiration from diverse sources such as mass media, history, personal archives, art, and everyday life, Sönmez seeks to construct a personal perspective that embraces the contradictions between individual and collective interpretations of time and history. Events and characteristics of the 20th century play a particularly significant role in his creative process. At present, he aims to bring together a spectrum of ideas through an experimental approach, weaving together various techniques and modes of representation — most recently turning to screens and hanging surfaces. This approach resembles a dismantling of the uniformity inherent in contemporary understandings of the relationship between individual and collective algorithms.

Central to Sönmez’s practice is his focus on the process of painting itself. The semi-abstract nature of his compositions further blurs the boundary between intention and chance, guided by improvisational exploration and generating a dynamic play between control and spontaneity. In some of his works, melted plastics and by-products of chemical processes bring spontaneity and freshness to the surface of the canvas, encouraging viewers to diversify their expectations of what a painting can be and to engage with the ethical, physical, and political dimensions of our relationship with the intertwined processes of mass production and environmental pollution. Fascinated by the transformation of personal and collective experiences, he explores this concept through the process of “sublimation”. His archive becomes a kind of archaeological quest, uncovering layers of both personal and collective memory as he delves into familiar motifs and reinterprets them. The transformation of these experiences into visual form is, in itself, an act of sublimation — where memories and emotions build compositions. This process allows for the merging of personal history with broader cultural references, offering viewers a glimpse into the artist’s psyche. Although recognisable figures and forms do appear, they are often veiled or fragmented. This is further intensified by memories from personal history, which Sönmez weaves into the fabric of his paintings. By avoiding purely narrative scenes, the artist invites viewers to interpret the works through their own experiences and knowledge.

Stories Behind the Paintings

1.

Let’s talk about the painting with Yuri Gagarin. It weaves together personal, political, and collective histories. Yuri Gagarin was my childhood hero — because I grew up in the Soviet Union, in Komi. My father worked there for ten years. I started school there. Today, the Soviet Union no longer exists, and that ideology has practically vanished – its discourse has disappeared. But we grew up with it.

After we moved to Turkey – a capitalist country – we were confronted with a different kind of propaganda: that of Western capitalism. The same ideological shift also began in Bulgaria. People who grew up in capitalist societies have no idea what we experienced in the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, we watched Hollywood films and stories, and from them we received something that strongly resembled Soviet propaganda. These symbols – for instance, Jurassic Park – also carry ideology, just as Yuri Gagarin was a hero of the Soviet one.

History is made up of layers laid upon one another, whereas at school, it is taught linearly. But I believe that in our brains, everything is tangled in absurd ways – without a clear line, without rational parameters. For me, images appear superimposed on top of one another, and they create a new picture, sometimes absurd – as in this case, where Yuri Gagarin appears at an audition for Jurassic Park. I also included this detail – Oliver Stone testing a mechanical robot that portrays a dinosaur. At the bottom I added flowers – lilies, lotuses. In order to bloom, they need stagnant, murky water. In this way, history becomes tangled and muddled – just like our minds. But out of that confusion, something positive, beautiful and meaningful can still emerge.

I experience social conflicts in a particular way – such as the one surrounding the so-called Revival Process in Bulgaria, as well as the tensions within Turkey itself: societal division, ethnic, religious, ideological, and class-based rifts. I connect all of this with my childhood and try to see it through a more naïve, childlike gaze – which, in my opinion, is the most truthful and realistic. Not the one clouded by ideologies and belief systems.

2.

“The Luxembourg Effect” takes its title from a phenomenon in radio physics of the same name, first documented by amateur radio operators in the 1930s. This effect, also known as ionospheric cross-modulation, occurs when signals interact in the ionosphere, reflecting and refracting radio waves. In a similar way, within the fragmented landscape of contemporary existence, concepts and ideas fly freely, and through the confusion of signals and meaning, we lose sight of what truly surrounds us. Amidst the noise, the process of meaningful understanding becomes elusive, and what emerges as a possible explanation for today’s lived experience is a vast, incomprehensible network composed of so-called “hyperobjects”. The effects and manifestations of these hyperobjects may be scattered across multiple locations, making their total form impossible to see or sense at once — thus challenging the very notion of subjectivity.

In this fog of uncertainty, individual experience fades, and we become oversaturated with messages — soon to find ourselves excluded, without ever understanding why it has happened to us. Today, artists engage with concepts and phenomena that are vast, complex, and often exceed the human scale of comprehension. Confronted with the deeply interconnected forces shaping contemporary existence, one fundamental question arises: How can art — and painting in particular — reflect such complex problems?

Şevket Sönmez