“Sofia–Istanbul: bridge of art. Artworks with Stories”,

an exhibition by Enakor Auction House

4 Dec 2025 – 3 Jan 2026 at the Union of Bulgarian Artists Gallery, 6 Shipka St.

Nurkan Nuf states that he creates conceptual art within the contemporary current of metamodernism, in which he “explores the interconnections between matter and consciousness, order and chaos, past and future—bringing them together in the experience of the present moment.” He transforms natural materials into tactile surfaces, upon which visual structures are constructed using a vertical plotter (a machine he designed himself), combining an organic and algorithmic character. These graphic configurations are based on mathematical models such as L-systems, inspired by patterns of natural growth. As he describes it: “I combine technology (the vertical plotter) with nature, the mysticism of Alevism, cosmological ideas, and conceptual oppositions.”

The Alevi Foundation

The previous sentence is not merely conceptual — it contains a golden well from which Nurkan Nuf draws with both hands. Alevism, part of his personal history, is not a theoretical resource but a living spiritual tradition that has survived through generations. It is woven into the earth, the body, ritual, song, dance, and silence — not as a quotation, but as a source. The circle in which bodies are arranged during the cem ritual and the sema dance; the words of Haydar Baba written on tobacco boxes — all of this speaks through his artistic language, even when he does not name it. In this art, which refuses to be titled, there are namings passed down not through words, but through soil and gesture.

To understand the layers from which this wordless naming emerges, we must return to its foundation — to the symbols preserved and transmitted by the Alevi tradition across generations. It is a heterodox current within Islam, with Shiite and mystery-based Sufi roots, rich in symbols and practices that incorporate elements from many ancient cultures — Christian, classical, Iranian, Anatolian, Balkan, and others. Among them are the geometric forms used by Nurkan — the circle, the square, and the earth itself.

In the Alevi tradition, the circle is not merely a geometric shape but a sacred model of existence — a symbol of perfection, the cycle of life, and the harmony between opposites. In the rituals of cem and sema, bodies are arranged in a circle — a space of equality, where the masculine and the feminine, the human and the divine, rotate in a single movement. The square is a form of stability — architectural, earthly, bounding. It outlines the stage upon which the circle unfolds. And when all three forms articulated by Nurkan — the circle, the square, and the triangle — come together, it is not merely a composition, but a cosmogony of the triad: “consciousness (circle), matter (square), creativity (triangle).”

In the Alevi and Bektashi world, earth is a sacred element — a symbol of humility, patience, and the eternal cycle. It partakes in the creation of the human being and reminds us of mortality (“we are made from earth and to earth we return”), but also of renewal — both grave and cradle at once. Earth from sacred sites, especially from Karbala, is revered as a bearer of blessing and memory: it is kissed, placed on the forehead, preserved as an amulet, put in the mouth or on the body of the deceased for forgiveness. In the cem service, it acts as a “witness” to oaths and repentance.

In the language of poetry, the earth is a mother and guardian of memory — she receives the seed, bears fruit, and is linked to the feminine principle. The ashik poets praise her as a faithful friend who reconciles the living and the dead. In the philosophy of the Path (Yol felsefesi), she is a teacher of humility, for in her there is no pride. In this context, earth is not merely a material — it is living memory and a creative womb, a mediator between body and spirit, between past and future.

Technique, gesture, trance

Nuf’s art does not begin with theory, but with the body. On a stretched surface of fabric, hazel branch, and twine, he spreads soil and latex with his hands. Then he lets the vertical digital machine — created by himself — draw fine lines, generated by an algorithm modelled after the growth of organic matter. These graphic configurations do not arise from the intellect, but from the interaction between matter and intuition, between unconscious gesture and mechanical precision. This is not painting to be looked at — it is skin that calls out to be touched, smelled, even tasted. It does not depict an image; it imprints a process of interaction. Its surface becomes thought, the thought becomes a sense, the skin becomes memory.

The account of directly mixing soil and latex on the canvas reveals an aesthetics of subconscious, uncontrolled movement — close to automatism, though not of the surrealist kind, but of an Alevi-meditative or chaosmosic order. This corresponds to Nuf’s concept of matter as intellect (he calls it “matter as consciousness”) — where the blending of materials is part of the very act of thinking, rather than simply a technique. Nurkan Nuf maintains that he works in a state akin to trance, with “minimised conscious or entirely unconscious control.” This is art born without titles or predetermined meaning — with a renunciation of authorship, not to evade responsibility but to share with the viewer. It is expressive, intuitive, even shamanistic — created in a primal bodily-mystical state.

In Nurkan’s art, the visual and the literary are interwoven. The text accompanying his works is written “in trance,” where genres dissolve “and everything flows from me in its natural course.” This intertwining of art forms is neither citational nor externally reflective. One does not “inspire” the other — they arise as different forms of the same inner movement. It is metamorphic art — not intertextual, but incarnational: it changes form without abandoning its essence. Moreover, when this metamorphosis encompasses not only matter but also meaning, a new language is born — one in which code and flesh speak simultaneously. His works are not the result of premeditation, but a surprise emerging from the very act of making. Yet, once they appear, they provoke thought; they open a space for understanding. There are no titles, no intentionally encoded meanings — but that does not mean they are meaningless. Rather, meaning does not belong to the author. The viewers are not invited to decipher, but to complete — to recognise themselves through the matter.

Interweaving Tradition and Technology

Where soil, latex, and the algorithmic fine-liner meet, a new material is born — neither fully natural, nor entirely synthetic. It carries the memory of the earth, yet speaks the language of code. Nuf’s gesture is both ritualistic and technological, initiatory and algorithmic. This is an art of interweaving: between flesh and software, soil and formula. Rather than opposing matter to machine, Nuf brings them together into a single organic body — the body of a new world that has yet to be named.

In his works, soil is not merely a background but a primordial ground where ritual and technology are woven together. It is the same sacred earth which, in the Alevi world, preserves ancestral memory and carries the promise of the future — a womb in which new life is conceived. But today, not only wheat sprouts from it, but also metallic wreaths, luminous fruits, and electric roots. The earth in his work remains a Mother, yet she now gives birth to both organic and artificial seed, binding past and future in a shared soil.

Three Bodies of Soil and Thought

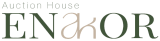

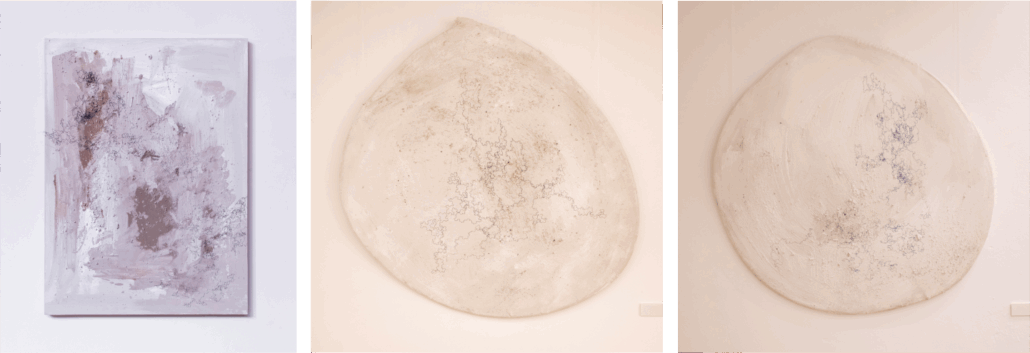

Nurkan Nuf takes part in the exhibition with one rectangular and two approximately circular works, made from soil, latex, twine, and fine lines drawn by a mechanical pen. All three pieces use soil as thinking matter — bearing traces of bodily gesture and algorithmic intervention. The forms correspond to the inner geometry of Alevi symbolism, yet are transformed into a sensory language that does not repeat tradition, but translates it through a new corporeality and technology. Nuf models dense, monochromatic bodies that invite you to touch them, smell them, and even taste them. They are flat and tactile — with soft, compressed volumes and a coarse texture. The movement within them turns inward — like pressure into the very body. The surface feels like something you have laid your palm upon. It is not an image, but the skin of a sense.

The rectangular form frames a state between order and chaos — begun, but unfinished — much like that Beginning in Hesiod’s Theogony, in which the history of the cosmos (order) emerges from Chaos, Gaia (earth-soil), and Eros: “Verily, Chaos came into being first of all; but next, Gaia, the broad-breasted, the firm foundation of all the immortals who hold the peaks of snowy Olympus… and also Eros, the fairest among the deathless gods.”

Hesiod’s account is not merely a Greek myth, but a literary reworking of earlier Near Eastern cosmogonies, originating in Phoenicia and Mesopotamia. This way of thinking about the Beginning — creation from earth-soil mixed with an element of divine body — stems from the lands of ancient Babylon. It is precisely there that Karbala lies today — whose soil Alevis still venerate as sacred, for it absorbed the blood of Imam Husayn, martyr and grandson of the Prophet. This appears to be the very same archetype that Nuf intuitively reawakens in the matter of his works.

The white-violet tones of the latex have spread thickly and expressively across large areas — but not everywhere. Patches of natural soil remain as shadowy stains, while other areas are covered only with a thin wash of colour. Some zones are densely charted by the thought of the mechanical pen; others are left open and unmarked. What is sealed here is a project of creation in motion — a process that the viewer is invited to complete and fill with meaning.

The circular forms recall ritual breads (such as peksimet) that Alevis distribute on Bayram Arife, or wedding loaves, and also the podnitsa — the earthen womb in which the sacredness of bread is kneaded and baked. Here, the soil is a maternal substance — trampled by feet, warmed by fire, imbued with ritual. These are surfaces of remembrance, where the human body and bread merge in scent and taste. The form evokes the sacredness of the circle in Alevi belief — women and men arrange themselves in a circle during the cem ritual, and in a circle, the steps of the sema dance are performed. The mechanical pen, with its tremulous motion, may be tracing the hesitant yet precisely ordered line of joined human steps moving in the rite with faith and trust.

Nurkan does not only sculpt — he paints. His colours are muted, softened with much white. The pen-drawn lines — with their black, delicate vibration — resemble at times a web of capillaries, at times a neural network, or a map of an unknown planet. They are at once biology and cosmogony — fractal paths of sensation, thought, and memory, inviting the viewer to carry them forward.

The New World — TechnoGea

The art of Nurkan Nuf emerges from a deep inner connection between the ancient and the new, between mystery ritual and technology, between cultural heritage and intuitive gesture. Through his works, he opens a path for those who do not yet suspect that such a path is possible. With his hands, he weaves together worlds that most deem incompatible: ancient flesh (soil, clay, ritual, faith, ancestors, fire, bread) and new matter (latex, digital language, algorithm), biological and electronic intelligence. In soil and latex, he fuses the sacred earthly substance with the synthetic medium. He unites mystical trance with machine precision. He refuses titles, yet possesses a conceptual apparatus as open as the code he uses. Alevi memory and digital aesthetics meet not in opposition, but as currents of a single stream of thought.

This is an art of co-existence — not human versus machine, not past against future, but an old soul in a new connection. Sacred soil receives artificial latex, just as artificial intelligence receives the aroma of podnitsa. The result belongs neither to the one nor to the other, but is a third thing, born of interweaving. Nuf connects the natural, the biological, and the electronic; the old and the new; ritual, faith, and code; mystery and algorithm; hands and logic — in a shared creative act that has no name yet. His model for a world, born between the past and a possible future, also has no name.

I would call it TechnoGea (from techne τέχνη — art, technology + Gea Γαῖα — Earth) — a world in which technology has grown out of the Earth and loves her. Code does not replace ritual, but translates it into a new language; algorithms and artificial intelligence do not override memory, but carry and expand it; the formula does not negate the body, but magnifies and uplifts it. This world lies beyond oppositions — biological/artificial, organic/synthetic, human/non-human. TechnoGea is a new cosmogony in which the creator is both electronic and embodied; matter speaks in symbols, and code remembers and writes a song; ancestral memory and data from the future merge. TechnoGea is a world in which new art is not “man versus machine,” but a hand that thinks digitally; a body that encodes; matter that dreams.

Nurkan Nuf has stood in the open temple of nature and of his Alevi ancestors, and fused it with his algorithmic plotter before anyone could tell him what to call what emerged. Now he utters it in the voice of the culture he inherits and extends. He utters it through his pioneering art. And the viewer will hear it.

Rossitsa Gicheva-Meimari, PhD

Senior Assistant Professor in the Art History and Culture Studies Section and member of the Bulgarian-European Cultural Dialogues Centre at New Bulgarian University

Biography of the artist

Nurkan Nuf was born in 1996 in the town of Razgrad, Bulgaria. He graduated from a technical secondary school and later pursued higher education at St Cyril and St Methodius University of Veliko Tarnovo, Faculty of Fine Arts, where he successively obtained both a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree. In 2024, he completed a PhD in the academic field of Art Studies and Fine Arts – Drawing. He is currently a part-time lecturer at the Department of Drawing within the same faculty.

Nurkan Nuf’s artistic practice is defined by a conceptual approach that explores the interrelations between matter and consciousness, order and chaos, past and future — bringing them together in the experience of the present moment. A key method in his work is the transformation of natural materials into tactile surfaces upon which visual structures are created using a vertical plotter — a machine built by the artist himself. These graphic configurations are based on mathematical models such as L-systems, inspired by growth patterns in nature.

Despite relying on strict formal principles, the process of creation remains intuitive and open to unpredictable interactions between materiality, technology, and personal expression. Nuf’s art does not seek to offer definitive meanings; instead, it functions as an open field for contemplation and aesthetic experience, inviting the viewer to immerse themselves and participate in a living, ever-unfolding interpretation of existence.

The Story behind the Artworks

In addition to my higher education in fine arts, I also hold a secondary diploma from a Technical High School, specialising in Electrical Equipment for Industrial Systems. I decided to apply these technical skills in the construction of a vertical plotter. Although my first attempt ended in failure (and even damaged my laptop), I gathered the courage to try again. Just before a trip to France, the machine finally began to function successfully.

During my visits to museums such as the Pompidou Centre and the Musée d’Orsay, I reflected on how I could integrate this machine into the narrative of contemporary art. This happened during the period of my doctoral studies, when I encountered the philosophy of metamodernism — a natural continuation of postmodernism, which seeks to reconcile opposing ideas and to search for sustainable answers to the challenges of the contemporary world.

In my art, I combine technology (the vertical plotter) with nature, the mysticism of Alevism, cosmological ideas, and conceptual oppositions.